Tell us a bit about how Red Rock Testimony came about.

The book has deep roots. Utah writers have a long tradition of writing in service of the conservation community. In the 1950s, from his perch in “The Easy Chair” column at Harper’s Magazine, Bernard DeVoto (born in Ogden, Utah) fired broadsides at those who would kill the wildness of the West. DeVoto then bequeathed his post as Voice for the West to his friend Wallace Stegner, who grew up in Salt Lake City.

In 1954, Stegner edited the first Sierra Club “battle book,” This Is Dinosaur, and when he wrote his “Wilderness Letter” in 1960, his definition of wilderness came right out of his childhood trips to southern Utah’s red rock country. The view from Boulder Mountain propelled him to that last soaring paragraph that ends with “the geography of hope.”

In the 1960s and ’70s, Utah wilderness became a national issue. Edward Abbey published Desert Solitaire in 1968 and partnered with photographer Philip Hyde on a Sierra Club book, Slickrock, in 1971. This was my coming-of-age time, and I began joining these battles as a writer and photographer just as the tragic and unnecessary loss of Glen Canyon, submerged behind a dam, galvanized my Earth Day generation.

And so, at the beginning of 2016, when a confluence of threats and opportunities surfaced in western wildlands, the Salt Lake City writing community began to meet, called together by a couple of long-time activists—all of us ready to take action, ready to immerse ourselves in this long tradition.

We had one remarkable campaign to support, the unprecedented Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition proposal. Five Southwestern Native nations had asked President Obama to proclaim a national monument on 1.9 million acres in southern Utah, to protect extraordinary sacred lands from archaeological vandalism and destructive energy development.

We also faced a whirlwind of threats that needed countering, notably the release of Utah congressmen Rob Bishop and Jason Chaffetz’s Public Land Initiative. This legislation promised to address the big issues on Bureau of Land Management land in most of eastern Utah with a “grand compromise” supported by all, but turned out to be both woefully inadequate as conservation and dangerously precedent-setting in its promotion of fossil-fuel extraction.

How could we participate in these conversations and affect these decisions with our essays and poems and stories? Our concerned group of citizen-writers had at least one model, a 1995 limited-edition chapbook called Testimony: Writers of the West Speak on Behalf of Utah Wilderness.

Terry Tempest Williams and I created Testimony twenty years ago at a similar moment of crisis. Congress was considering an anti-wilderness bill that would devastate Utah’s public lands. As colleagues and friends based in Utah, Terry and I decided we might have an impact by gathering short pieces from twenty writers passionately committed to preserving these special places. In just two months, we invited submissions, snagged a small grant to pay for printing, and took the chapbook to Washington DC, where we delivered a copy to every member of Congress. When Senators Bill Bradley and Russ Feingold successfully led the filibuster to defeat the bill, they read essays from Testimony on the floor of the Senate. When President Bill Clinton proclaimed Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in 1996, he told Terry that Testimony influenced his decision.

And so, with this 2016 round of attacks on public lands—and the promise of the Bears Ears monument—we asked: Do we need a Testimony II?

Kirsten Johanna Allen asked that question most forcefully. She is both an ardent conservationist and the publisher of the small, nonprofit, Utah-based Torrey House Press. She believed we needed this book, and she made the commitment to publish a trade edition after initial distribution of a chapbook.

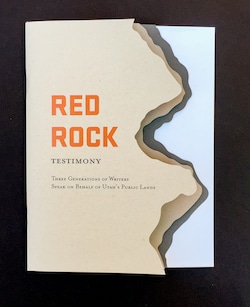

I volunteered to edit. With a bow toward the original Testimony, we called our new book Red Rock Testimony: Three Generations of Writers Speak on Behalf of Utah’s Public Lands. And, so, we went to work.

You have this history of using art as a tool for activism. How do you see the two braiding together or diverging in the present moment?

You have this history of using art as a tool for activism. How do you see the two braiding together or diverging in the present moment?

The internet has democratized art and extended the reach of activism since the original Testimony. From Tahrir Square to 350.org, we now know the power of digital organizing. As we created Red Rock Testimony, we talked a lot about how to reach our intended audience of decision makers in Washington—and how to broaden our reach in rousing citizens to action.

We wanted to make sure that Red Rock Testimony carried the voices of the writers as powerfully and directly as possible. We aren’t associated with any conservation group. This is meaningful literature in service to the cause, not just another rallying e-mail from the environmental community. And so we have a beautiful and arresting design by Tim Ross Lee that draws you in, and then we have faith in the abilities of our writers to move, rouse, and inspire. Elegance and eloquence still count in 2016.

We extend the reach of the print book with interactive website, www.redrockstories.org, which gathers work from everyone concerned about the future of southern Utah’s red rock wildlands. The stories in Red Rock Testimony form the bedrock for this nexus of artistic responses to that special landscape.

We raised money for the chapbook from individuals. In a few months, we’ll release a trade edition for general readers, with additional material.

Red Rock Testimony includes work from both native Utahns and writers from around the country. Why include the out-of-staters?

The southern Utah red rock wilderness belongs to us all. The 1.9 million acres of the proposed Bears Ears National Monument includes virtually no private land. This is public land—Bureau of Land Management land, National Park Service land, Forest Service land.

Plus, writers and citizens from everywhere love this place—and we wanted to emphasize that universality. So we invited nearly sixty writers to contribute, writers with ties to Utah, but well beyond the circle of people gathered in Salt Lake. We included as many Native writers as possible, since the Bears Ears proposal owes so much to the sensibilities, traditions, and vision of the tribes. (Who, by the way, are asking for co-management of the monument, a brand-new idea.) Charles Wilkinson, an Indian-law scholar who is volunteering with the Inter-Tribal Coalition, helped us to reach out to Ute and Zuni writers.

We knew we were on a tight timeline. We gave writers little more than a month to deliver their pieces—leaving just enough time for printing before we took the book to Washington in mid-June. The invitees responded with amazing commitment, nearly all sending original work. We received more submissions than we could fit into eighty-eight pages, the maximum length for a saddle-stitched chapbook.

Kathleen Dean Moore wrote her piece while on a San Juan River trip and fired off her draft when she got back to cell service. Gary Nabhan wrote his piece, about a transformative backpacking trip into the Bears Ears as a young man, while recovering from knee surgery, writing in the middle of the night when his post-surgical pain kept him awake.

In the final tally of contributors, about a dozen of our thirty-four writers hail from Utah. The writers in Red Rock Testimony range in age from Brooke Larsen (whose words open the book), born in 1992, to Bruce Babbitt, born in 1938. Three generations of writers come together here to speak for a place that all of them cherish.

They’ve created a community chorus, a montage of heartfelt words that includes Native and Hispanic voices, warnings from elders and challenges from millennials, personal emotional journeys, and lyrical nature writing. Their pieces address historical context, natural history and archaeology, energy threats, faith, and politics. Together, they offer a remarkable case for restraint and respect for this incomparable red rock landscape.

Red Rock Testimony braids essays and poems. How do you think these pieces together build a case for Bears Ears?

We know that great writing can make a difference. So we simply send these pieces on their way and believe that here and there a congressional staffer or a mid-level Bureau of Land Management administrator or a deputy chief of the Forest Service might pick up the book and start leafing through the pages. Maybe she lands on Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk describing being “floored by the amount of disrespect I received” when rudely cut off by the chair of a legislative hearing at the Utah capitol. (She tried to speak of the “personal healing like nothing else” that she finds in the Bears Ears.) Perhaps Alastair Bitsoi catches that reader’s eye when he says, “Bears Ears will always be a significant healing space for young Navajos like me, who live in the concrete jungle that is New York City.”

We purposely offer many ways into the argument for protecting these endangered lands. Charles Wilkinson begins the book with a quick survey of Colorado Plateau conservation that places the events of 2016 in context. Mary Sojourner tells of meeting a guy named Bear Campbell in a Flagstaff bar and going camping with him in the woods below Bears Ears. Amy Irvine watches southern Utah dust churned loose by cows and ATVs and oil and gas exploration blow eastward, turning the snowfields of the San Juan Mountains red. The darkened snow absorbs more heat, melting faster, overwhelming the reservoirs downstream—“meaning there [is] less water for big desert cities.”

Anne Terashima writes as a millennial grateful for time in the wilderness, a chance to disconnect from Instagram and Facebook. David Gessner ponders the “freedom of restraint” and concludes that “here freedom becomes more than a jingoistic word used to wage war and sell trucks.” And Bruce Babbitt makes the case for Bears Ears as a former cabinet member: “The best way to defend the Antiquities Act is for the President to use it.”

With luck, the book will land in the hands of Sally Jewell or Barack Obama, inspiring the administration to pursue the proclamation of a new and innovative national monument. Or perhaps Senator Dick Durbin or Martin Heinrich or Congressman Alan Lowenthal—all champions of southern Utah public lands—will find words to use when it comes time to lead the fight against bad legislation like the Public Lands Initiative.

We can’t know just when or how these connections will be made. But Red Rock Testimony provides elected officials and public servants in Washington, holed up in windowless offices and dreaming of slickrock and sagebrush, vivid validation for their work, an alternative to partisan anger, a celebration of the places they labor to protect. It’s a collection of the kind of writing that Ed Abbey called “antidotes to despair.

Above: Video from the press conference for Red Rock Testimony, held in Washington, DC, in June of this year.

The writing here creates such vivid pictures and narratives in the reader’s mind. What drives your belief in the power of art to not only help us understand our wild places, but help us defend them?

Those of us who write know how crazy we are to dedicate ourselves to this discipline. It’s insanely hard work to get every word right, rewriting and rewriting and rewriting. Though we may have few if any readers for some of our best work, we write because we have to. We write as an act of faith.

But as readers, we know the power of a writer to move us. I’ve sobbed at the endings of novels and memoirs. I’ve gasped and chortled and seethed with spitfire anger as I’ve read strong nonfiction. I’ve melted at the perfectly chosen images in poems. And I’ve learned the language of every landscape I love from reading the writers who made these landscapes their home territories in life and work.

Here I’ll quote from my introduction to Words from the Land, the anthology of natural history writing I edited in 1988. I began that piece by describing the power of writers who write about landscape. That gift remains as strong as ever, yielding words to help us understand, to spark us into acting on behalf of the places we hold dear.

What they hear in the earth are the voices of what Henry Beston called the “other nations” of the planet. In their prose, their translations of these voices, they teach us, by example, how to see more clearly and feel more truly; they put into graceful words some of our most euphoric and serious experiences. They strive, as Barry Lopez puts it, “to create an environment in which thinking and reaction and wonder and awe and speculation can take place. I have to trust that in so doing, that the metaphorical depth will reverberate there, and ideas much larger than ones I could control are going to come out.”

Comments

What a fine discussion, Steve. You are a very important voice for the west. As always, thank you for your words of wisdom.

Thanks, Steve and Orion, I was honored to be part of this book – in part because in these days of click and instagram and instant gratification, Red Rock Testimony is a real book – with pages and heart.

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.