My son has stage four cancer. I can write the sentence, and I can explain the diagnosis, but I cannot wholly believe it. Reason tells me that Jesse is likely to die soon, long before I do, but my heart rebels. Any parent who faces the prospect of losing a child to disease might feel the same. But not every grieving parent has written books celebrating the beauty, creativity, and glory of nature, as I have. Not every parent has declared in print, as I have, that nature is sacred. Now, dismayed by Jesse’s illness, I question whether my writing has paid sufficient attention to nature’s dark side. In seeking to defend the wild Earth against human abuse, have I taken too sanguine a view of wildness? Can I still celebrate a power that produces not only monarch butterflies, humpback whales, and sycamore trees, but also hurricanes, plagues, and cancer?

Jesse is forty now, the father of three young children. One spring morning when he was eight or so, he and I set out for a nearby park to play a game of catch. Eager to try out his new baseball mitt, he trotted along, and I hustled to keep up with him. As we came to the end of the sidewalk, however, he suddenly stopped.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“God is in the grass,” he said, his voice quavering. “I can’t step on it.”

I gazed down at the grass, each blade gleaming in early sunlight. Mint-green leaves sprouted from every tree, the wind brought a heady fragrance of lilac and dirt, birdsong laced the air. If there was divinity anywhere, here it was. So far as I knew, nobody had taught Jesse to see God in the upwelling energy of spring. Perhaps, on sensing that energy, he simply gave it the grandest name he knew, a name he had learned at the dinner table and in Sunday school.

After a brief negotiation, Jesse allowed me to pick him up and carry him piggyback from the sidewalk to our favorite spot for playing catch. Evidently he did not worry that I might offend God by walking on the grass, nor did he object when I set him down. He pounded his mitt, I moved away, and we began tossing the ball back and forth. The game seemed to distract him from his fear, for soon he was racing over the grass to catch the pop-ups I threw. But when we decided to go home, he asked me to carry him until we reached the pavement. As he rode on my back with his legs clamped around my waist and his arms around my neck, I smelled the sweet perfume of his sweat, the sweat of a boy too young to know that one day he would die.

The expression on Jesse’s face as he stared at the spring grass showed a mixture of wonder and terror, an emotion I knew well from my own childhood glimpses of nature’s daunting power. By the age of ten, a couple of years older than Jesse was that day in the park, I had seen lightning shatter a giant oak in the front yard of our farmhouse, had narrowly escaped from a river in flood, had stumbled through the wreckage from a tornado. I was well acquainted with the death of animals. In our chicken coop I found hens gutted by raccoons; in the pasture, I found one of our colts sprawled on the ground, crawling with flies, stinking, its belly swollen from eating rotten apples. I watched my father skin and butcher deer he had killed, watched him pluck the quail and pheasant he had shot, watched him scale and fillet fish. Already, by the age of ten, I had twice come close to dying — once from bee stings, once from falling through ice while checking muskrat traps. These brushes with death made me realize that what happened to animals would eventually happen to me.

To speak of nature as sacred is to say it is of utmost value, independent of our place or our fate. To speak of nature as holy is to acknowledge it as the force that generates and shapes everything.

The only alternative to oblivion, I had been taught in church and Bible camp, was to earn admission to heaven. In the rural Methodist churches my family attended, there was an emphasis on works rather than faith, perhaps because our fellow worshippers were farmers, carpenters, electricians, factory workers, and homemakers who lived by the sweat of their brow. The God invoked in those churches could damn us to hell, but would prefer to grant us eternal life. The good Lord yearned to save us from death, we children were told, a yearning summed up in the claim that God is love.

But if God is love, I could not help wondering, what rival power accounted for all the unloving things I observed? The drunken fathers, battered mothers, families broken by divorce, ragtag kids boarding the school bus hungry, dogs flattened by cars, stillborn rabbits, bums sleeping in barns, robins torn apart by hawks. In other congregations, all that misery might have been blamed on Satan. But among those country Methodists, if your crop failed because of drought, or if a fox gobbled your chickens, or if lightning set your house on fire, or if cancer stole your child, you didn’t blame Satan, and you certainly didn’t blame God, for that would have called your religion into question. No, you blamed nature.

Nature was the name for everything that people did not make and could not control — every bout of bad weather, every biting insect or snake, every weed and blight and disease. Rats raided your corncribs. Deer darted across the road in front of your truck. Trees crushed your roof. Wind and rain stole the dirt from your fields. In Sunday school, we learned that our bodies — but not our souls — were part of nature: corrupt and rebellious, the cause of drunkenness and fights, drag racing and short skirts, lustful boys and pregnant teenage girls, deformed babies, and early deaths. To my young mind, this troublesome nature appeared to be a primal force on a par with God, but lacking love.

Even as I took in this fearful view of nature, I was forming a very different impression while exploring the woods, fields, and creeks near our homes, first in Tennessee and later in Ohio. I climbed trees, watched squirrels and butterflies and beetles, turned over rocks in search of crawdads, studied tadpoles in pond water, squished barefoot through mud, inhaled the dust of fallen leaves, filled my pockets with seeds. What I found in those remnants of untamed land did not frighten me. There were no big predators that could make a meal of me. The worst danger I might run into was a patch of poison ivy or a nest of yellowjackets. Sure, I noticed rotting stumps, fur scattered around an owl’s kill, bugs tangled in spider webs, blossoms trampled underfoot. But I was young, my body brimming with energy and free of aches. It was easy for me to ignore the shadows in God’s Creation.

That the world is a Creation, not an accident, I firmly believed. For in childhood I had been taught that everything in heaven and on Earth is God’s handiwork: the sun and moon and stars, the oceans and dry land, the butterflies and buttercups, the mosses and midges and great whales, and every creeping, crawling, flying, sprouting creature. Having made the world, God looked upon it all and found it good. Or so I read in the opening chapter of the Bible. But this teaching made me question once again how benevolent God could be. For if the Creation is good, the work of a loving Creator, why is it filled with suffering?

The answer I heard in church was that God sent trouble our way as a test of faith. After hearing that claim from the lips of preachers and Sunday school teachers, I found it dramatized in the Book of Job. I first read Job’s story when I was twelve. I know how old I was, because I keep within reach of my writing desk the Bible given to me on my twelfth birthday by my step-grandmother, who inscribed the date in her flowery cursive. By then I was beset by dread of death, so I scoured the tissue thin pages, searching for a key to eternal life. I read the Bible as I read any other book, straight through from first page to last, proceeding over the course of many months from Genesis to Revelation.

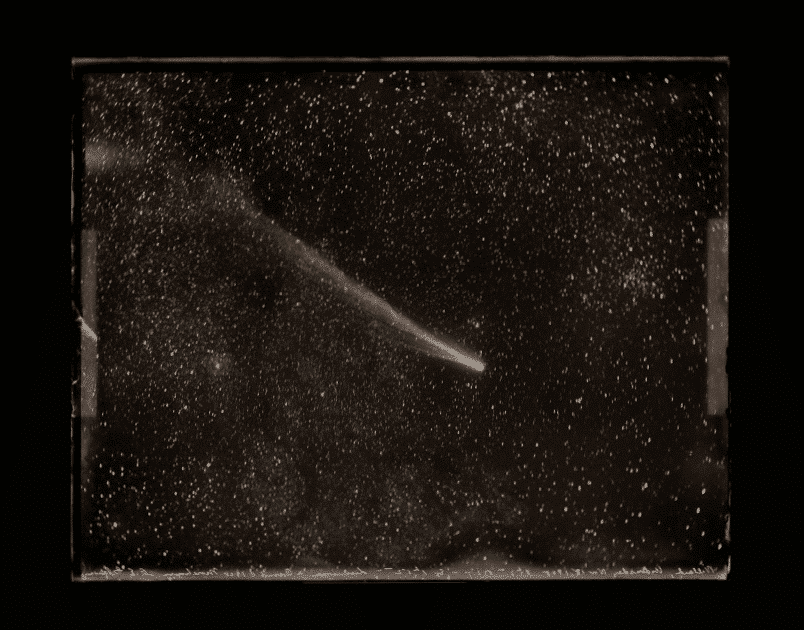

comet morehouse, november 18, 1908 (university of california, lick observatory)

Thus I came upon Job long before I read about Jesus. Even as a young and frequently baffled reader, I could easily follow Job’s story. He is a good man, careful to obey all the religious rules, and yet he loses his wife, his children, his livestock, and all his worldly possessions, everything but life itself. His friends tell him that he must be guilty, a secret sinner. But Job insists on his innocence. He demands to know why a just God would inflict such misery on a righteous man. Finally, God answers out of the whirlwind:

Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? . . . Have you commanded the morning since your days began? . . . Have the gates of death been revealed to you, or have you seen the gates of deep darkness? . . . What is the way to the place where the light is distributed, or where the east wind is scattered upon the earth? . . . Can you bind the chains of the Pleiades, or loose the cords of Orion? . . . Do you give the horse its might? Do you clothe its neck with mane? . . . Is it by your wisdom that the hawk soars, and spreads its wings toward the south? (Job 38:4–31, 39:19–26)

It’s a thrilling speech: seventy verses long, a catalog of nature’s wonders, aimed at making any paltry human tremble before the grandeur of the Creator.

The speech culminates in God’s challenge to Job: “Shall a faultfinder contend with the Almighty? Anyone who argues with God must respond.” The only response Job can muster is an abject apology:

I know that you can do all things, and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted. . . . Therefore I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know. . . . I had heard of you by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees you; therefore I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes. (Job 42:3–6)

Following this apology, the story closes with a few verses telling the reader that Job’s fortunes are restored twice over, including seven sons and three daughters to replace the ones he lost, plus thousands of sheep and camels and oxen — a happy ending as contrived as anything dreamed up in Hollywood. Such restitution, we are told, compensates Job “for all the evil that the Lord had brought upon him.” Why the evil was brought upon him to begin with, except as a cruel test of faith, is never explained.

In my early reading, I kept looking for an answer to Job’s question, which had become my question: If the Creation is good, if God is love, why is there suffering, sickness, and death? Eventually I realized that the story of Job provides no answer. The speech attributed to God does not explain why the wicked flourish while the innocent perish, why we must pass through the “gates of deep darkness” and ultimately through “the gates of death.” The speech merely warns uppity humans like Job not to ask such questions, lest they anger the Almighty. Since I knew the Bible had been written by people, not dictated by God, the lack of an answer to Job’s question meant that those who composed and preserved his story could shed no light on the darkness of Creation.

While I was doggedly reading the Bible, three or four pages per night over several years, I was also reading books on science from our public library. I followed my passions: fascination with dinosaurs led me to study evolution; model rockets led me to astronomy; birds and bugs led me to biology; rocks led me to geology; kitchen table experiments led me to chemistry and physics. When I had exhausted the offerings in the young adult section, I moved on to the books for grownups. On the advice of a teacher, my parents bought me a subscription to Scientific American, a magazine that reported new discoveries along with the rigorous methods by which they had been achieved. The passages I could not understand — and there were many — only inspired me to deeper study. While my Bible reading was dutiful, homework for graduation to heaven, my reading of science was driven by curiosity and delight.

By the time I started college, science had displaced religion as my principal guide for understanding the universe, the nature I observed around me, and my own life. There was no sudden moment of conversion, no angry rejection of my earlier training, but rather a gradual letting-go of one authority in favor of another. The imaginative reach and rational power of science captivated me. The universe it revealed was more expansive and more astonishing than the one depicted in the Bible or preached from the pulpit. Unlike biblical stories, those told by science — about the Big Bang, for instance, or evolution, glaciation, photosynthesis, plate tectonics, genetic inheritance, mass extinction, or the growth of a fertilized egg into a human baby — could be tested, refuted, revised, or replaced. The scientific enterprise was cumulative and cosmopolitan, drawing on discoveries made by countless people, across hundreds of cultures, over the course of centuries. Science was not pinned to the pages of scripture, fixed forever like a fly in amber; it was dynamic, constantly evolving, like the organisms and cosmos it sought to understand.

In the light of science, Job’s question evaporated. Suffering is a puzzle only if one assumes that the universe is ruled over by a benevolent deity who cares about our well-being, and who responds to our appeals for relief. Drop that assumption, and the destructive side of nature becomes neither evil nor good, but simply the way of things. In the universe described by science, there are no angels looking after us, no saints to answer our petitions. Nor is there, within our mortal bodies, any essence that will outlast death. At the age of seventeen, a college freshman studying physics and math, I thought I had freed myself from all such illusions.

At the age of seventy-two, I recognize how much of my childhood religion lingers in me, and how little consolation science offers for the prospect of losing my son.

Today, at the age of seventy-two, veteran of many losses, I recognize how much of my childhood religion lingers in me, and how little consolation science offers for the prospect of losing my son. My wife and I learned about the severity of his disease piecemeal, as he did, over the course of the past year. In May 2017, he consulted a doctor about lumps on the side of his neck, and was told not to worry, they were merely lymph nodes swollen by infection or stress. No stranger to stress as the manager of a business in Washington DC, Jesse accepted the diagnosis. But in the fall, as the swellings on his neck hardened, he sought another opinion. Thyroid cancer, the second doctor told him in late October, an affliction that in most cases can be effectively controlled by surgical removal of the gland followed by treatment with radioactive iodine. The prognosis for such cases is good, with a ten-year survival rate of better than 90 percent.

Then, in mid-November, a biopsy and blood test revealed that Jesse had medullary thyroid cancer, a rare and aggressive form of the disease, occurring in roughly 4 percent of cases. MTC, as we learned to call it, does not respond to radioactive iodine or to any other chemotherapy. Still, if the cancer was confined to his thyroid, the oncologist told him, removal of the gland should prevent it from spreading. In January, surgery disclosed that the cancer had already spread to tissue beyond the thyroid and into dozens of lymph nodes along the sides of his neck. This finding meant the disease was, at best, in stage three, implying a ten-year survival rate of 70 percent.

In early March, a blood test to measure the level of the hormone marker for MTC yielded a number much higher than the last measurement taken before the surgery, indicating that the cancer had metastasized beyond the thyroid and lymph nodes. A PET scan showed the cancer had entered Jesse’s spine, pelvis, femurs, and other large bones. Thus, step by disquieting step, he was diagnosed with stage four medullary thyroid cancer, for which there is no known cure. The estimated ten-year survival rate ranges between 20 percent and 40 percent.

He may be one of those who survive, not only ten years but longer. That is what I fervently wish for him, so that he may live to see his children grow up, live to do the work he feels called to do, live to keep company with his wife, live to outlive me. If he dies before I do, my knowledge of nature will not spare me from grief. The Japanese poet Kobayashi Issa, a devout Buddhist, knew that everything passes, a human life as surely as a drop of morning dew. When his own child died, however, he confessed his anguish in a haiku, here translated by Robert Hass: “The world of dew / is the world of dew. / And yet, and yet—” In that phrase “and yet” I hear the heart’s refusal to accept what reason declares to be the way of things.

In sharing this personal story, I do not mean to impose my grief on readers, for we all have more than enough griefs to bear, both public and private. I tell of Jesse’s cancer because it has made clear to me the persistence of those questions, intuitions, fears, and longings that inspired my early devotion to church-going and Bible-reading. I still puzzle over the sources of suffering; I still experience wonder and terror and awe; I still yearn for a sense of meaning; I still seek to understand the all-encompassing wholeness to which I belong. When I moved away from the cramped, anthropocentric world of biblical religion, I carried those old feelings with me. I found a new home for them in nature — in the intimate nature of Earth and its creatures perceived through my senses, and in the vast, evolving, exquisitely ordered cosmos, from subatomic particles to distant galaxies, unveiled by science.

When Blaise Pascal confessed in his Pensées, “The eternal silence of these infinite spaces fills me with dread,” the space he had in mind was cozy compared to the one we know. At the time of his writing, in the mid-seventeenth century, on a clear night in France he could have seen with his unaided eyes at most a couple of thousand stars. Even with the recently invented telescope, which enabled Galileo to spy the moons of Jupiter and discern individual stars in the Milky Way, Pascal could not have seen more than a minuscule portion of the universe disclosed by modern instruments.

avalokitesvara, the great bodhisattva of compassion, 14th c. meditation cave, saspol, india

The current estimate for the number of stars and galaxies is so staggering that scientists resort to imagery in an effort to convey the abundance. In the PBS documentary Cosmos, first broadcast in 1980, the astronomer Carl Sagan made the often-quoted remark that there are more stars in the observable universe than there are grains of sand on all the beaches of Earth. In case you are skeptical of that claim, as I was, let me note that several pundits have shown that the math checks out, even based on a conservative estimate for the number of galaxies. More recently, with the benefit of observations provided by the Hubble Space Telescope, the physicist Chet Raymo has calculated that there are more stars in the Milky Way galaxy than there are salt grains in ten thousand pounds of salt.

I have abandoned the religious creed in which I first encountered words like soul, sacred, holy, reverence, divinity, and awe, but I refuse to abandon the words themselves.

Moreover, astronomers now suggest that the mass and energy bound up in all those uncountable stars and galaxies make up only about 5 percent of the universe. The remaining 95 percent, labeled dark matter and dark energy, has so far not been observed, but only inferred from its gravitational effects. The existence of so much hidden mass-energy helps to explain, for example, why a spiral galaxy such as ours does not fly apart, and why the rate of expansion of the universe is accelerating instead of slowing down. To add yet another layer of weirdness to the current scientific cosmology, some physicists speculate that the universe we inhabit may be only one of a potentially infinite number of alternate universes.

All of this dizzying array, whether in a single universe or many, imbued with life only on one planet or on billions of worlds, is what I mean by nature. The term embraces black holes and black bears, moons and microbes, quasars and quarks and quail. Contemplating such a vision, I feel wonder and terror in about equal measure. When those emotions combine, they produce awe, and awe is the root of reverence. To speak of nature as sacred is to say it is of utmost value, independent of our place or our fate. To speak of nature as holy is to acknowledge it as the force that generates and shapes everything. It is our source, our sustenance, our home. It is the divinity we can sense and study. We can behold the sun and moon and Milky Way with our naked eyes, can delve into the depths of space with our ingenious instruments. But the only portion of the sacred universe that we can affect, for good or ill, is here on Earth.

In moving from a religious worldview acquired in youth to a scientific worldview developed in adulthood, I have followed a pattern common among American nature writers, including great pioneers such as Emerson, Thoreau, Muir, Leopold, and Carson, as well as accomplished contemporaries such as Barry Lopez, Terry Tempest Williams, Chet Raymo, John Elder, Kathleen Dean Moore, Pattiann Rogers, and David James Duncan. In each of these writers, one finds, to varying degrees, patterns of thought and language carried over from religion. In particular, no matter how thorough their conversion to science, they maintain a sense that our relation to nature is essentially moral. They call on us to preserve Earth’s beauty and abundance, not merely to assure our survival, but to honor the intrinsic value—the sacredness — of nature. Without appealing to a Creator, they look upon our planetary home and find it good.

Even though Pascal’s religion assured him that humans are at the center of the universe, and in the care of a benevolent God, he clearly had his doubts. For in the Pensées, he attributes his dread not so much to the overwhelming scale of those infinite spaces as to their eternal silence. The stars wheel on, remote, indifferent. They offer no comforting messages, no guidance, no answers to prayer.

As our friends learned of Jesse’s illness, several of them promised to pray for him and his family. I was touched by their kindness, and grateful, even though I had long since folded up my prayers and put them away along with other mementos from childhood. How many times had I recited at bedtime that unsettling rhyme?

Now I lay me down to sleep,

I pray the Lord my soul to keep,

and if I die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

How many times had I recited the Lord’s prayer in church? How many clumsy pleas had I whispered into the darkness, shaken by fear or confusion or desire?

The study of science convinced me that there is no cosmic Lord monitoring our pleas, no sympathetic ruler who will intervene on our behalf to alter the course of nature. And yet on walks in recent months, retracing paths my son and I have taken together, I often find myself murmuring, “Heal Jesse, heal Jesse,” over and over again, in time with my steps. At first, when I caught myself repeating this refrain, mildly embarrassed, I would still my tongue. Yet within minutes, as I continued my walk, the words would rise again: “Heal Jesse, heal Jesse.” Eventually I gave in to the impulse, and now I let the words come. When I cross the park where Jesse sensed the presence of God in the grass, my chanting feels very much like prayer.

Why do I chant? Not because I imagine some deity might grant my wish. Not to elicit sympathy from passersby who might overhear my muttering. I chant because the repetition steadies me, the way a mantra centers the mind of a meditator. It calms my tumultuous feelings and concentrates my thoughts on what matters, as reciting the rosary or the psalms grounds believers in their faith. My calling of Jesse’s name is timed to the rhythm of my footsteps, my breath, my heartbeat. A mother’s heartbeat is the first sound we hear. Once outside the womb, we respond to that rhythm in the beating of drums, in the bass notes of music, in the iambic pentameter of poetry. Describing prayer in terms of physiology rather than theology does not make it any less comforting. Instead of appealing to an otherworldly spirit, prayer becomes a way of communing with earthly life, a reminder of our kinship with everything that breathes.

The study of science fosters a greatly expanded sense of kinship, one that stretches from the dirt under our feet to distant galaxies. Exploding supernovas produced the calcium in our bones and the iron in our blood, along with all the elements heavier than helium that make up our bodies, our built environment, and our rocky, watery globe. We are kin not merely to a tribe or nation, not merely to humankind, but through our genes and evolutionary history we are linked to all life on Earth, plants and fungi as well as animals. We are made for this planet, creatures among creatures.

If you put your hands in the dirt, for example, and then use them, unwashed, to bring food to your mouth, you’re likely to take in a microbe called Mycobacterium vaccae, which triggers in your brain a burst of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that will lift your mood and sharpen your thinking. So the smell of thawing soil in spring rouses us from our winter slumber, children make mud pies, and gardeners eagerly dig. Our bodies are ecosystems, habitats for hundreds of species of microorganisms — some of them harmful, most of them beneficial. The strictly human cells in our bodies are outnumbered ten to one by the trillions of bacteria, viruses, and other microbes that live on us and inside us, fellow travelers on the evolutionary journey. Altogether, a person’s microbiome may weigh five pounds, while her brain weighs about three.

These discoveries and thousands more come to us as revelations, not from scriptures or God but from sustained inquiry by our three-pound brains. What humans have learned about our world and ourselves is no doubt dwarfed by what we don’t yet know, and may never know. Still, it’s amazing that a short lived creature on a dust-mote planet, circling an ordinary star near the edge of one among billions of galaxies, has managed to decipher so much about the workings of the universe. And the more we decipher, the more we realize that everything is connected to everything else, near and distant, living and nonliving, as mystics have long testified. This connectedness, this grand communion, is what I have come to think of as soul — not my soul, as if I were a being apart, but the soul of Being itself, the whole of things.

I have abandoned the religious creed in which I first encountered words like soul, sacred, holy, reverence, divinity, and awe, but I refuse to abandon the words themselves. For they point to what is of ultimate value, what claims our deepest respect. As a writer, I wish to say that nature is sacred, deserving of reverence for its creativity, antiquity, majesty, and power. I wish to say that Earth is holy, precious, surpassingly beautiful and bountiful, deserving of our utmost care. Although our survival is at stake, an appeal to fear won’t inspire such care, because fear is exhausting and selfish. Although we need wise environmental policies, laws alone will not elicit such care, nor will a sense of duty, shame, or guilt. Only love will. Only love will move us to act wisely and caringly, year upon year, all our lives long.

The meaning of the word love was also first framed for me in a religious context. As a boy, when I still watched baseball games on television, I would often see, in the bleachers behind home plate, a man holding up a sign that read, JOHN 3:16. This verse from the New Testament was one of many I knew by heart: “For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him shall not perish but may have everlasting life.” That promise of salvation from death is what fills the pews in Christian churches and fills the coffers of televangelists. I understand the appeal, though I no longer believe in the promise. The root of the word nature means to be born. But that is only half the story. The fate of everything born, whether star or child, is to die. Whatever nature knits together, it eventually unravels.

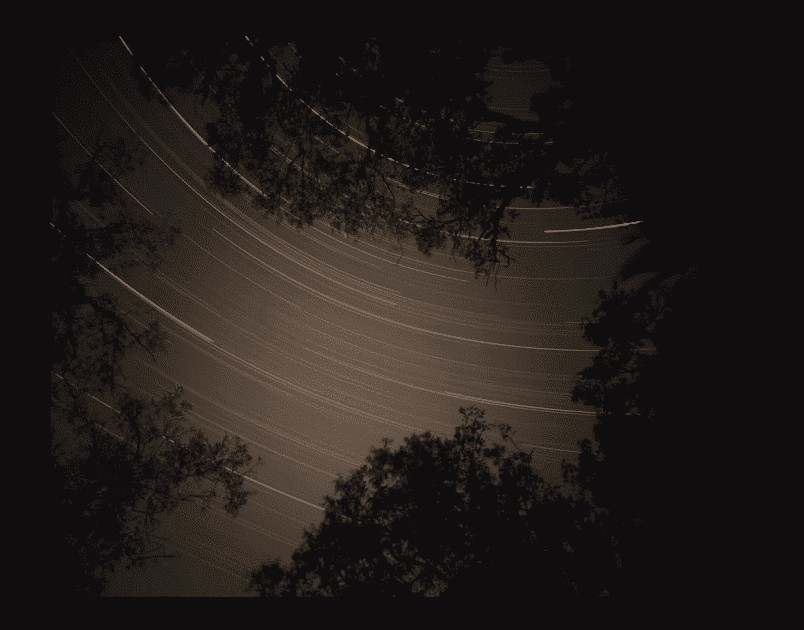

southern sky, australia, 1997

Cancer is one of those ways of unraveling. There is nothing unnatural about cancer, although the toxins and radiation we introduce into the environment surely increase the incidence of this and every other form of disease. Neither is there anything unnatural about an animal defending itself from predators and pests. That’s why our species has a robust immune system, which controls most pathogens from outside our bodies and most rogue cells inside. That’s why, when the immune system falters or fails, we turn to medicine, including a battery of therapies to resist cancer.

The only therapy Jesse receives at present is a monthly injection of a drug that strengthens bones, to reduce the likelihood of fracture. A lifelong athlete, he began with our games of catch in the park, then moved on to basketball and soccer, but now he has been ordered to avoid contact sports and give up running. He may continue training with weights, to preserve the strength in his bones, but he must be careful not to fall. He must caution his rambunctious five-year-old son not to run across the room and leap into Daddy’s lap. The boy and his two sisters, ages eight and ten, know that Daddy is sick, but they do not know how sick. Nor would you know, if you met Jesse today, for the cancer does not yet show in his posture or his walk. But the disease is working in the marrow of his bones; the cells multiply and proliferate, claiming more of his energy, more of his body, day by day.

I write these lines in May, a year after the first doctor told Jesse that the lumps on his neck were nothing to worry about. Had that doctor sent him to an endocrinologist, the cancer might have been detected before it spread from his thyroid, or at least before it invaded his bones. It might have been caught in time for healing. The analogies to our environmental crisis are obvious. As a nation, as a species, we risk ignoring climate disruption, soil erosion, mass extinctions, collapse of ocean fisheries, and other ecological warnings until the damage is beyond repair. The drive of cancer cells to multiply and spread is no different from the impulse that drives humans to reproduce and spread our kind around the globe. Unlike cancer cells, however, we have the capacity to reason, to foresee consequences, to change our ways.

Whether there is a Creator who loves the world, I cannot pretend to know. But we are the ones, we humans with our insatiable appetites and disruptive technology, who need to love our bit of the world, this magnificent planet. Think of how you love your child, if you have a child, or how you love the children of others — the toddlers learning to walk, the kids pumping their legs on swings, the teenagers holding hands. Think of how you love whatever you passionately love: music, flowers, painting, poetry, baseball, language, dance, the first frog calls of spring, the return of sandhill cranes, the sound of rain on a metal roof, the full moon in a clear night sky, the splash of the Milky Way, every atom and whisper of the one with whom you share your bed. That is how we must love the world.

Comments

Thank you, Scott Russell Sanders, for this deep, unguarded, heart-opening look into the nature of nature, the nature of existence, and the losses we face. May we all love as much of it as we can.

Sending love and healing wishes to your family. You were my professor in college at IU Bloomington in the ninties. I still quote you “Every time we buy something, we are voting.”

My thoughts and — yes, prayers — for you, Dr. Sanders. I met you years ago, when you read here at Alfred University. In the midst of some of my own dark times, your writing has comforted me. Read and writing, I believe, are prayer too.

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.