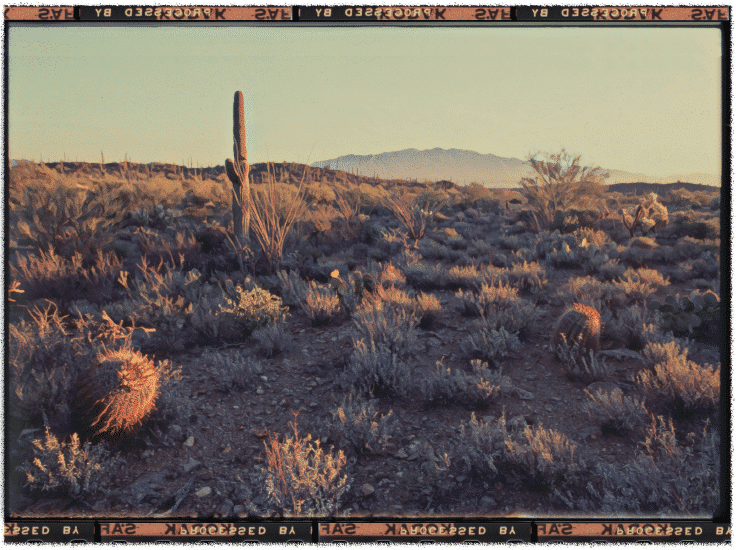

HEY, MR. ABBEY, can you hear me down there? This yolk of sun has broken on a horizon sawed in two by saguaros and I’ve hopscotched my way through crypto and cacti, sidestepped a sidewinder, and given two middle fingers to an Air Force jet that buzzed me while my pants were down to pee on the playa. And now I’m squatting graveside in this lower Sonoran desert that is your resting place⏤a desert that has, thank the horned gods, not succumbed to the Mad Max lunacy in Moab.

We should talk. About the redrock country of Utah. Desert Solitaire was published fifty years ago this year, and as timeless as that book is, things are changing in ways even your prescient, nimble mind could not have imagined.

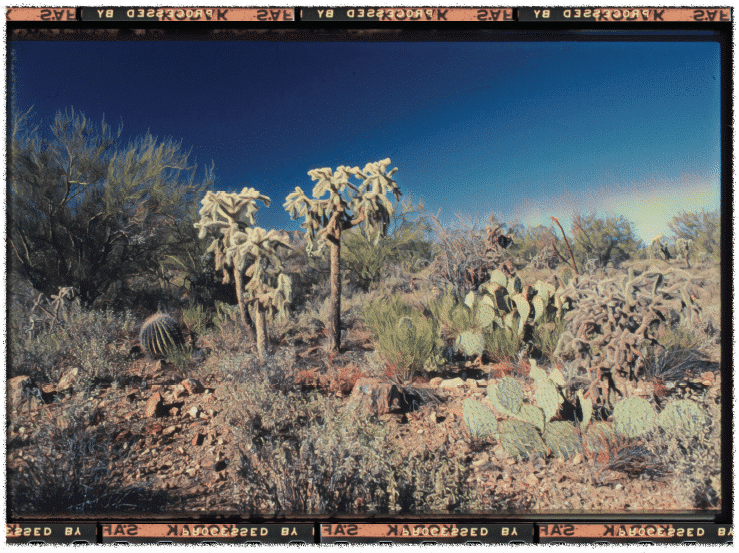

I’m going to sit here a minute and take in the surroundings. This is a desert more soft and yielding than southeastern Utah’s, one less feverish in color, less tortuous in form. It’s a bit easier to breathe here, isn’t it? This place doesn’t excite⏤not the way canyon country does⏤the extremes in our nature. And it holds the whole of the borderlands⏤both sides⏤ denying our tendency toward sharp stark divisions and dumbed-down dualities. So it’s interesting, Mr. Abbey, that you chose here, to lie in situ⏤given your aversion to immigration. Then again, maybe you wanted to return to Arches for a perennial season⏤but the park’s tumescent popularity would have dissuaded. After all, you predicted rightly that the solitude you found there once upon a time was a much-diminished resource; if it was going, going, it’s now nearly gone. In Arches, your bones could not possibly turn to dust in silence.

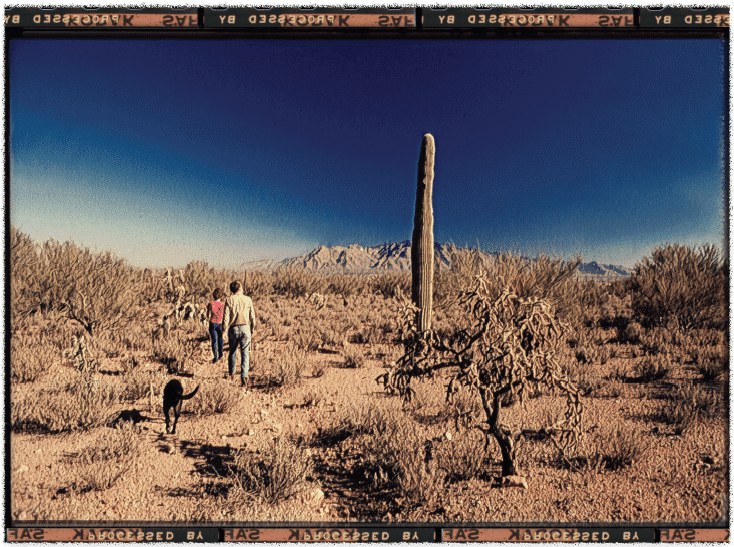

And that’s why I am here today. To talk to you about solitude. Both the lack of it and the need. You see, it’s getting pretty crowded, even in Utah, where public lands once felt infinite. I wonder if we know anymore what your definition of the word even means⏤the feeling that is not loneliness but “loveliness and a quiet exaltation.”

So I hope you’ll come up and sit with me. For we must chew on this notion of what solitude was, and now is. I’d suggest a walk⏤knowing we’d both love to roam under this honeycomb of sky that drips early morning gold onto spindly arms of ocotillo, through the pale pink translucence of jackrabbit ears. But I’m guessing that’s a lot to ask at this point, given your twenty-nine-year repose. Why don’t we just sit, dig our heels into these still-cool volcanic ball bearings that masquerade as soil. I promise to seek some semblance of restraint. It won’t be easy. The questions, the concerns⏤they threaten to rush from my body like a river freed from a blown-up dam.

Tell you what. Let’s start with what is panoramic, and political. How about I rant for a bit, before working down to what is personal. And then we keep going. By nightfall, let’s hope we hit bedrock⏤that naked, common ground.

By the way, I covered my tracks. If word got out, the GPS plot points would be posted on the Internet (long story, that) and you’d never know another moment of posthumous peace. Rest assured I got here by stealth, and now I’m sweaty, squatted, and waiting on the parched, prickly kind of land we both love. The shadows of vultures cut across my skin. They think I’m dead but never have I been so alive! Because despite what seems like increasingly dark times for the planet, these wild places persist. Places that exfoliate our neuroses. That refuse to coddle our compulsions. That remind us, in these times of profound greed, what we really need.

About Moab: you can probably imagine the jacked-up monster trucks, maybe even the Razors⏤these golf carts on steroids, the least sexy form of transportation known to man. But I bet you can’t fathom the BASE jumpers⏤that’s right, people now don shiny, baggy disco suits and leap off the tallest red cliffs like flying squirrels. There are also beefed-up all-terrain bikes that can circle the White Rim in a day, if you’ve got the quads for the job. And those delicious, hidden swimming holes in Millcreek Canyon? Some days the Bureau of Land Management has to dose off access⏤because several hundred people are already writhing in them amid a thick scrim of sunscreen, Jaeger, and Red Bull. The entire city, the surrounding valley, Behind the Rocks, and beyond emit an ever-present belch of engines, shine Lycra, and sweat caffeine. As for Arches⏤no matter where you stand in the park, you can hear the steady roar of it all. Everywhere you look there are these hyped-up, tricked-out, uber-fit, machinelike humans that pump, grind, climb, soar, and scramble through the desert so fast they’re just a muscled blur. The land’s not the thing, it’s the buzz.

So there’s work to be done. Our public lands⏤the West’s de facto wilderness, its national parks and monuments⏤they are endangered in ways we never conceived of. Utah is in the worst shape⏤so many of its incomparable wildlands were protected within two of the nation’s newest national monuments but our so-called Commander in Chief has filleted each one, leaving only the stark bones in custody. This dismemberment of the Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante, two places you knew and loved, represents the largest maiming of public lands’ protection in the nation’s history.

This means the green light is brighter than ever for the usual suspects of industry and motorized yahoo-ism, but the land is threatened by our ilk, the muscle-powered outdoor wanderers, too. Which is to say you, Mr. Abbey, may have developed whole fleets⏤generations’ worth⏤of desert defenders, but now they’re out there en masse, bumping into one another on the very ground on which you taught them to go lightly and alone. They are as much the problem as they are the solution, and it’s hard to know how we don’t divvy that down the middle, into us and them, right and wrong.

Your headstone reads, NO COMMENT, but I’m hoping to discuss what we do next. You should know up front that I’m admiring, but not starstruck. You got some things right, but you got other things wrong. Like calling the desert “Abbey’s country.” Can you imagine, in my own book about Utah, if I had called it “Amy’s country”? I could have justified it; my family has been there for seven generations and counting. Yet even with such credentials the clan of my surname doesn’t get to call it ours because it’s all stolen property: whatever the forefathers didn’t snatch from the region’s Native Americans on one occasion, they took from Mexico on another. But that’s what the white man does. He comes in after the fact and lifts his leg on someone else’s turf. You, sir, were no different.

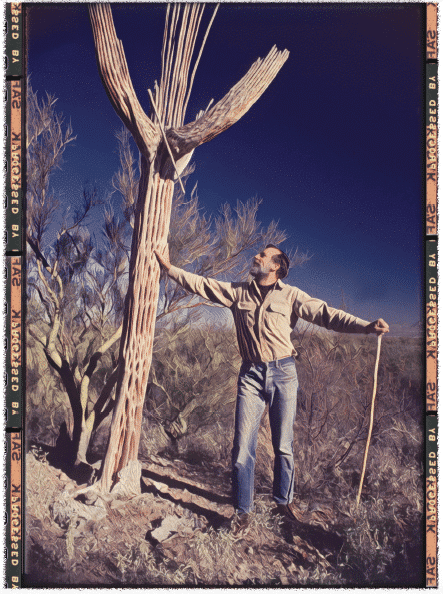

Another thing: there’ll be no chumminess today. I won’t be calling you Ed, or Cactus Ed⏤although your fans do. They have good reason for assuming familiarities. When Desert Solitaire was published in 1968, you crowbarred open the American consciousness and the red raw desert strode right in. Like a cocklebur caught in a coyote’s tail, you went with it⏤indistinguishable from all the convoluted canyons, scoured-out washes, mesas tiered like wedding cakes, mercurial creeks, rasping whiskers of bunchgrass, and the obsidian objections of ravens. There were also those geologic, gymnastic backbends⏤your beloved arches.

The New Yorker called your book an “American masterpiece.” And sure enough, by the time the ragweed, dust, and scree of those essays settled, all of what you had to say took up some serious psychic real estate. You, Mr. Abbey, still lurk there. Like Hitchcock shuffling through his own film, one might not even notice you. But you’re present all right, even as you bask in the director’s chair. Desert Solitaire framed the American West through your lens, and so we see through the glass brightly: the Utah desert is not just a place to explore, not just a resource to exploit. It is a body⏤both politic and erotic. In every way it’s scandalous.

Your claiming of Utah’s desert outback taught an entire nation what it means to be in collective possession of a place. At the same time you taught us that one’s interest in national lands is not a given⏤although the idea of it certainly is. It is only truly ours after we have gotten out of the car and wandered far enough off the trail to get lost and use up our last drop of water. Only after we’ve been out enough times⏤to draw blood, fry skin, write eulogies, pull stakes, see ghosts, and duct-tape a flapping sole⏤should we feel in possession of them. But those of us who have done our time out there know this is the mirage, the trick of light on water that is actually scoured sand. It’s the rough country, after all, that’s in possession of us and not the other way around.

Look, it’s early. But I’ve primed the old Coleman and the coffee is on.

I’M CAFFEINATED NOW, and pacing around the mound of grit heaped over what’s left of you. The sky is a primrose, blooming far beyond the margins of this place, this state, this nation. A sky that shows us how not to crouch too tightly over what we claim as ours. That reminds us how to reach for, and touch, what is Other.

Circling back to the notion of informalities: I just can’t. Hence the Mister. I’d like to keep some boundaries between us and a bit of decorum is good for that. Precautions must be taken because, as I packed for this journey, our mutual friend and iconic bookseller Ken Sanders reminded me that it wasn’t just that women hurled themselves at you⏤you did plenty of your own hurling, too. Sure enough, a few months before you passed away, my mother drove to Sam Weller’s Zion Bookstore in downtown Salt Lake City, where she stood in line for you to sign a copy of The Fool’s Progress, which she gave to me for Christmas that year. You were nearly dead, but you hit on her. This was despite the fact that she’d read nothing you’d written. Nor was she one to wander through the desert outback. Apparently, you knew how to travel between topographies.

Another mutual friend, Charles Bowden⏤God rest his seared, singular soul⏤was a known womanizer too. And for both of you, much has been made of this, and perhaps unfairly. Meaning you weren’t exceptional⏤in this way, anyway. Men juggling multiple women is a common and long-standing tradition in the West, if not the world. My ancestors were all polygamists, as was John Singer, the man who fixed our television before dying in a shoot-out over homeschooling his kids. And a girl from a similar arrangement beat the ever-loving shit out of me on the playground the year before she was taken out of school to be married. We were in sixth grade at the time.

But things are changing on this front too. While you’ve been underground, rubbing elbows with grubs and worms, a new narrative has been in the works. For instance, there’s now this thing called #metoo. (It’s used for a type of brief, mass communication called “tweets,” which in this case have nothing to do with your beloved canyon wren, or any other bird for that matter.) The rules of engagement between men and women⏤even when consent is mutual⏤have been seriously upset. No one is sure of how we are to deal with each other now, but however it shakes out, I’m pretty sure you won’t like it. You don’t get to gawk at co-eds anymore⏤not without consequence. And it’s no longer charming to describe us as rosy-cheeked skinny dippers⏤even if Katie Lee considered it a compliment.

This is not to say that I’m some shrill, ball-biting feminist with a bone to pick out of your saltbush beard. Nor am I implying we neuter or tie a tourniquet around our time together today. That would be like smothering this desert with blacktop, concrete, and a strip mall⏤but come to think of it, things here, around your grave, aren’t as peaceful as this still morning would have me believe. Did you know that in the last few years at least ten thousand miles of renegade roads have been gouged into the surrounding wilderness? Not by recreational motorheads, like those in Moab. But by the United States Border Patrol. Its agents know no limits, when it comes to sniffing out tens of thousands of desperate Latinx people⏤only to turn them back toward the desperation. That is, if they’re not indefinitely held against their will in encampments far too similar to Hitler’s. The patrollers even seek and destroy the food and water caches left for the border-crossers by bleeding-heart types. This cruel effort ensures that many will perish out here, halfway between two worlds⏤worlds even this desierto cannot fuse.

Here, in this place where you asked to be buried on the sly, I guess it’s fair to say that its solitude is an illusion. Come to think of it, you were rarely solitary in Arches. There were cattle roundups with caballeros, there was barroom banter with yellowcake miners, and there were rivers run with friends. And when you were working in that trailer, scribbling away in those notebooks the desert’s details that would become a bible for the desert brethren⏤there was a wife. There were children. And there were other women. I know it’s a device, writing as though one were alone when in fact one is not. And it worked. Everyone who read that book took to the desert solo. Self included. When I first read Desert Solitaire, I was single and free. It was easy to follow suit. But now that I have been a working mother wrangling a special needs child in a complicated and congested world⏤my definition of solitude has changed.

Which reminds me, I’ve been wondering about a line from that book of yours: “If we could learn to love space as deeply as we are now obsessed with time, we might discover a new meaning in the phrase to live like men.”

I get the part about space and time. Every cell in my body would trade the latter for the former. But the phrase that you chose to italicize … what did you mean, “to live like men”? I get you meant we’d quit racing like lab rats toward sugar, to fill every moment with tributes to all things temporal. And of course, you meant let’s not fill every acre with reminders of our species. But were you also contemplating our urge to fill the other side of the bed or the unclaimed stool in a bar?

I’m with you, on forsaking time. On embracing space. But while we’re at it, let’s find out, too, why we cling to the contrary.

And for parity’s sake, let’s find out what it means to live like women. Or perhaps we should say, let’s find how women like to live. I don’t think we’ve ever been asked that question. The results could be revolutionary. Evolutionary. We might become a new species entirely.

LOOK AT THESE GUNS OF OURS , all sleek and gleaming in that now-wretched sun. Literally, they are too hot to handle. But they remind me of this other thing I want to talk about, which is why I have carried a firearm in the wild. More than once I’ve come too close to feeling like prey⏤and I don’t mean for cougars, bears, or wolves.

I am a kid. My family is camping on the Green River. In the night a man enters a neighboring tent and puts a knife to the throat of a woman while her husband and children beg for her life.

I’m twenty-something. At home on the road, I travel from one climbing area to another, when another female climber goes out for a run and is taken by a man who kills women for sport.

I’m a new mother nearing my fortieth birthday. I kneel on a dirt road and try to change a flat tire when a truck full of men on meth starts circling like a shark. Brandishing the tire iron, I run at the truck and scare them away, but still, you can imagine.

All of these moments happened on public lands. While I would give every limb to have had your job in Arches⏤the nearest human being twenty miles away and little but a resident rattlesnake to guard the perimeter⏤I must say, the thought also scares me. I don’t suffer from hysteria, as Freud would have you believe. In the United States, a woman is raped every two minutes and 81 percent of us have been sexually harassed. Meaning the vast majority of us have feared for our jobs or our lives. You might be shocked to hear that, just as you might squirm when I tell you that most mass shooters and serial killers⏤we have a lot of them these days⏤are white males.

Something has got to give. Because the thing that came to mind when I read how you floated down the river with Newcomb was the time I was on a remote stretch of a similar river when a man with needle tracks on his burned and shirtless arms stumbled out of the shadows and began to threaten my three friends and me. The strapping guys in our group escorted him out of camp and back up some old Jeep road from whence he came, but you see my point. Solitude, for women, is a different animal entirely.

I’m not trying to paint your gender to be all bad. I came to love the wild world by way of boys and men; it was they who taught me to hunt, climb, paddle, build fires, read maps, ski, and throw knives.

Of course, in the beginning, there was my father. Our first adventure in my memory took place on a dark tongue of river, in eastern Utah, just below Flaming Gorge Dam. It was Memorial Day weekend. I was eight and my sister, Paige, was six. The first morning, the weather was unseasonably cold and gray, with a damp velvet hand that was hard to shake. The spring runoff had been let loose from behind the dam; the river was fast and high. As my father shoved away from the shore, my mother expressed her doubts⏤which my father promptly blew off, and this wasn’t the first time he’d done that. An hour later, when the high winds howled upriver and the waves rose like mythic sea creatures to greet them, his response was to whoop with glee⏤a feat, given that his mouth was occupied with the stub of a Swisher Sweet. He refused to put down either fishing rod or cigar to steer the boat. Not even for the big sinkhole toward which we were headed.

I was kneeling in the bow of the boat and felt a kind of awe. The latex floor of the vessel was gelatinous beneath my small bony knees, and through it, I could feel the current. I also felt the sheer force of the water as it sucked the raft up and over the swell, before it slam-dunked the boat into a dark and foreboding sinkhole. I wasn’t old enough to know that my father should have turned the boat perpendicular beforehand, that coming in sideways in such a small watercraft was very poor form indeed.

I clung to the bowline and squinted as the water hit my face. My mother and sister screamed and my father grunted with a perverse pleasure. And then, just like that, the raft popped out of the hole and we were moving downstream again, and fast. My father tossed me a metal Folgers can and I bailed like mad. But my hand forgot the task⏤it hung suspended between the scoop and dump⏤because I was looking back for one last glimpse of the hole. My dad barked at me then, to keep bailing. Above the roar of the water and the wails of her youngest daughter, my mother cursed from the top of her lungs at the man she had married but would soon divorce.

Another bend in the river and wind slid the raft sideways across the water, like a knife cutting across a cake. It rammed the boat into a sheer cliff with a sharp overhang⏤cut from eons of water banking steadily off it. The overhang was just at head level, so my mother put out her hands to keep the edge from nailing my sister’s skull. She bloodied her palms in the process. As my family sailed backward past the take-out, my dad’s paddling was at last the priority but now pointless. A man onshore saw the trouble we were in and dove into the swift water, which I recall as frothing and bottle green. He grabbed the line my father tossed but couldn’t find his footing. He too was nearly swept away⏤until other folks on the bank rushed in and pulled to dry ground the man, the raft, and my sodden, sputtering family.

That trip ruined it for my mother and sister. Squelched the whole outdoor adventure thing. The week after, in the supermarket, my mother ran into a woman with whom she played bridge and held up her hands. I hid behind the half-full cart as my mother recounted the story, to which the woman shuddered and said how it was just like a man to put his family in that precarious position.

Here’s the thing: my mom and sister stayed in camp the next day, but I got back in the boat. And when I was soaked to the bone and my lips a cadaverous shade of blue, my father finally noticed and steered the craft⏤this time with success⏤to a small beach beneath a rock alcove, where he built a fire of pale gray driftwood. As the smoke and heat rose to lick the stone ceiling overhead, hundreds of fat, black spiders dropped down from the huecos in the overhang. They dangled from their threads, inches from my face. I wanted to scream, with so many, so close. But I was with my dad, crouched in a cave, the fire’s warmth seeping into my skin. The two of us shared a bag of waterlogged beef jerky. It was the most delicious, primal food I’d ever eaten.

In that moment, my father was my locus Dei. Just as he was that night in camp, when he put a pistol to the ribs of the man holding a knife to that woman’s throat. After that, for far too long, I would deify the guys who followed. And in this way, I missed what you, Mr. Abbey, described as the “rainbow-colored corona of blazing light, pure spirit, pure being, pure disembodied intelligence, about to speak my name.” Which means that when I was tucked under that overhang of stone as porous as a sun-bleached skeleton, spiders waving on air like prayer flags and the meat on my tongue like an offering, I failed to hear the roar of the river as the chanting monks in the temple, brothers and sisters in the tabernacle. It was the calling to enter into communion with not just one man or one god⏤because oh, how those two get confused. Not even with one creature⏤say, a horse⏤but with every being in the whole wide web of the world, each of us, a sacred and vital strand.

NOW ABOUT YOUR DESCENT into Havasu: it sounds like my idea of a delightful trip. Especially the part where you got good and stuck in that slot and braced for a long, painful death. You called it one of the happiest nights of your life. I’ve had trips like that one that left me benighted atop L’Aiguille du Midi in Chamonix, and another in Utah’s Dark Canyon Wilderness, where getting lost for a night meant waking up to a roar and running for my life as a flash flood came careening around the bend.

These experiences are signs of lives well lived. So I guess we’re not much different than Aron Ralston or Dean Potter. Getting to the outer limits of oneself, even if we don’t return with all our parts, even if we don’t survive, is what puts us in touch with our animal selves, the place in which physical hungers sharpen but material longings lessen. At last we are in the moment where every breath, every bead of sweat, matters. Let us not forget, though, that to move through the natural world in this way is a privilege that belongs to the able-bodied, upper classes. Those well educated, well employed, and mobile enough. Those with the means and free time to make the trip.

Which leads me to another issue. This time with your Conradian moment in Havasu, where you delighted in “going native,” a phrase that sits squarely in the same province as “Abbey’s country.” Now you’re probably rolling your eyes down there, thinking that I’m flashing some PC badge at you, but it’s so much more than that. Our kind can go primal, we can go feral, we can caterwaul, and go AWOL, but we hardly know what it means to be native to anything anymore.

You likely meant it tongue in cheek, but I hiked into Havasu Canyon the year after a Havasupai Indian killed a female tourist, stabbing her twenty-nine times. I’d carried my daughter in; the camping gear came on the backs of god-awful-looking horses and mules driven by men who never smiled. While the rest of our party was out hiking one day, I took Ruby to the waterfall. Pebbles pinged around us as we waded in the aquamarine pool. Then the stones hit closer, and they were bigger. I looked up to the cliff tops, where a young local man in a Denver Broncos shirt scowled plainly at us. Being spotted didn’t stop him from throwing more rocks. I scooped up Ruby and hurried back to camp⏤a camp so large and packed with tents and stoves it could have been a refugee settlement. Except that these were mostly white people who had paid top dollar for their gear as well as the chance to enter the only portion of Grand Canyon National Park to be commanded⏤if you can call it that⏤by a Native-American government.

The rest of the village was in bad shape, and its residents cool to us, at best. I wasn’t surprised, seeing as most tribes have been relegated to postage stamps of land and subjected to endless cycles of poverty, disease, abuse, and addiction. It wasn’t until we hiked backup to the rim that I learned about the murder the year before, and how insult had added to injury. By the time I arrived, tensions were at an all-time high between tourists and residents. Since the murder, investigators had heard from women who’d been assaulted in Havasu Canyon but hadn’t reported the attacks. Such cases involved young male tribal members as well as a large white man who called himself “an Indian sympathizer.” He slept in the bushes and partied with the locals in an attempt to “integrate.” On two separate occasions, a woman hiking alone was grabbed from behind by a man who tried to pull her off the trail; luckily, both women got away. One investigator went on record saying that women shouldn’t hike alone in Havasu Canyon⏤it was just too dangerous.

So don’t be that creepy white dude who’s trying to siphon a sense of meaning and belonging off the desert’s native peoples, Mr. Abbey. They have enough troubles.

And for godssakes. Leave the women be⏤or you might get punched, kicked, maced, or worse. We’re a little on edge these days.

I MEAN NO OFFENSE, Mr. Abbey. But here at the end of our time together I’ll confess that Desert Solitaire didn’t wow me to life-changing, yogic extremes. I chalk it up to being born here, in Utah. Every family endeavor⏤hunting, fishing, raising cattle, camping, skiing, and more⏤having happened on its public lands. Meaning much of what you noted in that book was something I had already noted for myself. I knew the species, the sensations, even before I had the words to name them.

But there came a day in high school when the boy I loved left me for, in his words, “some fresh action.” My grades tumbled. I swapped the Go-Go’s pop music for Suicidal Tendencies’ punk. All because of a boy, I became everything I wasn’t.

My English teacher, Mr. Krenkel, noticed and kept me after school one day. He was wearing a HAYDUKE LIVES! t-shirt because a local television station had visited earlier that afternoon to do a story on test scores or some stupid thing that you would surely have scoffed at. The principal had asked the male teachers to wear dress shirts and ties, the female teachers to wear skirts. He’d asked me too, as class president and occupant of other esteemed positions that reflected my compulsion to overachieve, to please take the safety pins out of my ears and leave the leather jacket and combat boots at home.

So I’m standing in Mr. Krenkel’s class⏤he in his Hayduke shirt and me in my anarchy garb⏤and he hands me a map of the Escalante and a copy of The Monkey Wrench Gang. For spring break, he says, circling on the map the location of Hole-in-the-Rock Road, and the head of Coyote Gulch. Go there. I say I’ve already been, with my dad. He says go again, but only after you read this book. I’ll fail you if you don’t.

I see now. Before that book, I’d taken the Utah wilds for granted. Assumed that it was safe because it was at the heart of God’s gift to my ancestors. Besides, the best places were federally protected as parks and monuments and wilderness. Back then, I still believed such lands, their designations, were inviolate.

I went home and read about Doc Sarvis and Bonnie Abzug and Seldom Seen and Hayduke himself⏤and I was gobsmacked. I could resist authority! I could act on behalf of my heritage, by which I don’t mean my Mormon ancestry but rather these beloved public lands! I packed up my Plymouth Champ and, with the punk-rock boyfriend who succeeded the first heartbreaker, drove south. We took LSD and headed into the canyons that now make up the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, me with my dad’s Kelty pack, the bottom of its external frame whacking the backs of my knees. I hardly noticed, because I fell in love in a whole new way. Not with the boyfriend, or the drug, but with the desert. Another wilderness activist was born.

AND NOW, MR. ABBEY, that sun hangs like low fruit on the western horizon, and all around us the brown-skinned people to the south have begun to steal through the pooling shadows, where it’s hard for the snipers to see them. As for me, I’m hungover and my thighs need a spatula to scrape them off this chair. I’m also wondering what the hell there is for dinner. I’ve brought my throwing knives, and I’m getting pretty good. Perhaps if I huck them out into the desert, I’ll get lucky and hit a rabbit⏤a thought that I know makes you wince but right now I’m hungry enough to suck up my humane tendencies. Then again, if I throw into the dark I might puncture a water jug that could otherwise save someone’s life.

Oh, the choices. And our complicity. Since your time in Arches, the art of survival, just like the search for solitude, has gotten far more complicated. I’m all talked out. I had so many questions, so many narratives to pitch at your more dominant one⏤which I’m not faulting you for, by the way. After all, it was handed to you.

Forgive me for saying this, but from where I sit, you’re not quite the maverick you once seemed; I see your clones all the time and they are mostly male and devoid of much pigment. Even my friends, my fellow wilderness activist colleagues⏤men who say all the right things in the presence of women and the underrepresented others⏤they have made damn sure their places are retained at the head of the table, above the glass ceiling. Meaning I’ve been talked over, talked down to, hit on, and underpaid by those guys⏤and they are the closest thing I will ever have to brothers.

But I am not here to suggest we go our separate ways, we men and women. Lord knows I’ve had enough of that, and I’m betting you have too. In fact, there is nothing I want more than to go home to the blue-noted, flagless man, and I’m guessing you pine for your beloved in the same way.

Which leads me to the thing I’ve most wanted to say today: Would you mind me revising that phrase from the book⏤the one I lifted for my first wedding invitation?

What if it read: Love flowers best in close quarters?

It’s not a question, actually. It’s a must. We are on our way to being crammed together like cows in a feedlot. To survive without turning into heartless monsters, or soul-sucked automatons, we’ll need intimacy with people every bit as much as with place.

The wound, the anger and apathy that masks it, is what drives us to be le solitaire⏤which in French refers to one who is isolated, a kind of “lone wolf.” But the French form also means “tapeworm.” Going it alone is a failure of contribution and compassion, and this is what drains the world dry⏤of fossil fuels, of hope and joy.

Ultimately, this is why I am here today: to invite you to join me in asking your followers to do away with their rugged individualism⏤which I never bought anyway. By nature, we are a cabal. A group gathered around a panoramic vision. A group gathered to conspire, to resist. This is vital to our survival, as institutions fail and tyranny threatens. Believe me when I say that our democracy, with its wide but firm embrace of the last best wild places, has never been so jeopardized.

I actually prefer the French term, cabale. The e makes it a female noun, and that rings true about now. While cabale means political conspiracy and intrigue, it is imbued with spiritual and mystical meanings, too⏤and I’d say the divine thing we’ve been given is nature itself⏤both ours and the land’s.

Our most precious resource now is wonder. What we wonder about ignites our imagination, unleashes our empathy, fuels our ferocity. We fold in on ourselves, a thunderous, galloping gathering, a passionate, peopled storm, nearly indistinguishable from the ground on which it rains, on which it sprinkles seeds. This is how hope takes root. What springs forth are monolithic possibilities.

Despite all the bad news, the monarch butterflies, once in desperate decline, have returned. For the first time in decades, a wolverine was spotted in Michigan. In defiance of Trump’s predatory agenda, a coalition of 15 U.S. states, 455 cities, 1,747 businesses, and 325 universities has proclaimed its commitment to the Paris Agreement, which seeks to rein in the horrific effects of climate change, on behalf of the American people. Today’s millennials, a new generation of voters and consumers, have also unified and mobilized to shrink humanity’s gargantuan carbon footprint. The snow leopards, four thousand in number and growing, have moved off the international endangered species list. Mexican fish are proved to be having cacophonous orgies, and California condors⏤of which only twenty-two individuals existed not long ago⏤now have numbers in the hundreds, some of them in southern Utah. Colonies of microbes have banded together in the ocean to devour swirling islands of human-generated trash. And get this: I saw two wolf pups and heard the howl of an adult⏤somewhere far from where wolves have been documented in the West. I won’t say where, because it’ll get them shot, but the wolves are spreading out, into the lands we love. Into Abbey’s country. Amy’s Country. The people’s country. Which was Canis lupus country all along.

Wait, before I head out, let me look in my pack. I’ll have to dig through the rocks, snakeskins, and feathers collected on my way out to your final address⏤and yes, here it is: the original Desert Solitaire manuscript, with line-edits and corrections made by your own hand. It’s a marvel, to hold these pages, typed by your fingers just a few years before I was born. Be patient, please, while I flip through this draft…there, I ‘ve found it…a very up-front reference to your wife and kids! Here, unlike a few other glossed-over mentions in the book⏤places where you dissemble and joke enough that we believe the nuclear unit to be hypothetical⏤it reads that you were a family man!

Why did you delete this line? Why is it that the juniper tree and the scorpion figure largely on the page when the people you loved do not?

This is so hard for me to understand. Because I write about the broken hearts. The infidelities. The suicides and separation of siblings. Perhaps this is the way of women: we seek not so much solitude as solidarity, intimacy more than privacy. But it’s the way of wilderness too⏤in a thriving ecosystem, integration matters far more than independence.

There is the adventure that traverses the land, that excites and restores. But there’s also an inner landscape⏤its fiery furnace of the heart, the natural bridges built between beings. So I say to you, go solo, into the desert. Yes, do this and love every minute. But then come back. Come fall in with the cabale that has joined together, to save what we know and love. It will take multitudes to slow the avalanche of apathy. And it will take a lot of devotion.

The bats are bombing me now. And something large just passed by⏤whether it’s a jaguar or a human heading north, I do not know. Really, they are one and the same, part of the world community to which we all belong⏤now, more than ever.

So thank you. For inviting us into Abbey’s country. A lot of us grew and healed there. And we learned too what a privilege it is, to be stewards of these incomparable lands, to have the liberty to speak and act on their behalf. There, our hearts grew beyond the personal⏤with its small and selfish love affairs. But now our hearts must grow even beyond the political. Whether we’re talking about the naked desert or the body, let us no longer duel in dualities.

Perhaps I can call you Ed, now that I’m packed up and headed home. Kind of like the way we never speak to the folks we sit next to on planes and then suddenly we’re all chummy as we prepare for landing⏤that rough, bumpy drop onto sweet bedrock holding the boundless whole of who we are: paradoxes, half-truths, and all. O

—

This essay is from Desert Cabal and appears with permission from Torrey House Press and Back of Beyond Books. Photography by Hans Teensma.

Comments

This is a masterpiece! I too was captivated by Desert Solitaire and Abbey when I was young. But after reading more of his writings I became uneasy and aware that I wasn’t included when he spoke of mankind. Later in life I had a name for it: mysogyny. He hated women. Now I can appreciate the gift he gave me and other women: I love the solitude of the Colorado Plateau, the Mojave, the Sonoran deserts, and the high arid expanses of the Great Basin. But I cannot embrace the masculine mystique he embodies. I think quite possibly he would have encouraged the macho intimidation techniques men employ to terrorize solo women. Thank you Amy, you perfectly described my reality of Edward Abbey.

Very fine writing! (Yes, I definitely have to purchase the book.) I really enjoyed this generational update for 2 slightly perverse reasons. First it shows that Abbey is and will remain a classic for all the agonistic influence we would like to suppress, poor old Harold Bloom’s suddenly in desert and the French “cabale” has a dessert Kabbalist telling us about a new generation’s correct misreading. Abbey had the grace of outrage to ask the right questions that are more relevant than ever about our relation to wilderness. Second, Irvine hits o what I thnk is the great problem of our time. At a time when the cretin in Washington shrinks wilderness and parks, people forget that Abbey wrote when world population was about 3.5 billion. It is now 8.5 billion and headed for 11.5 billion by 2050. Nobody distributed all the condoms, as Abbey advocated! Just as the world today has the same volume of freshwater as it did at the birth of Christ, the amount of wilderness for which a growing populations thirst has not grown. Demands and impacts on the parks do, and Irvine is right, we have to Change and move beyond Abbey’s doctrine of rugged individualism, and we have to do so quickly.

I read Desert Solitaire, Dharma Bums, and Monkey Wrench Gang when I was 16 in the early 1990s

Your essay captures so much honesty about folk heroes and changes in engagement with wild places. I struggle with the shifts from Solitude to live streaming, and experiencing wild to online campground reservations and action sports.

Thank you

A beautiful piece and so many poignantly-true bits in here. There is one piece I deeply disagree with: women and solitude in the wild DO go naturally together. To generalize that all women seek solidarity over solitude overlooks the experience of many women, myself included. It would have landed more squarely had the author kept this sentiment to herself; that she prefers solidarity to solitude.

We absolutely love your blog and find many of your post’s to be exactly I’m

looking for. Does one offer guest writers to write content in your case?

I wouldn’t mind publishing a post or elaborating on a number of the subjects you write in relation to here.

Again, awesome web site!

A well written article but I wonder why the trend now is to review someone’s life under the current social and political climate in effort to criticize the works of those who came before us. I find this to be an ever increasing trend in the environmental community to focus for on slights to our sexual or national origin rather than continue to focus on the destruction of our environment. Yes I would disagree with Abbey’s love of guns and as to is immigration policy – possibly it was simply saying there are too many of us. We cannot continue to frame our conversation based on the slights ( or even the horrors) of the past, our sexual identities, our national origin. We need to take the great ideas of all and try to use the ideas to our benefit irregardless of the rough edges that are part of humanity.

What was the point of this article? ‘Colourful language’ does not create meaning by itself and this article is a great example. Lots mentioned but nothing said. Garbage.

Yo, Paul – your socks are showing.

Subtle and extravagant, entertaining with a central message: we must all cabale!

I knew Ed, and know that he did love some females. All the women I knew who knew Ed enjoyed his company and liked him. It is weird to read someone’s view who only knows the author through their books. The writing and the writer exist in different planes. He enjoyed sportyakking and liked to take a daughter with him on the Green. He was a good guy, a fair writer, not a Stegner or Lavendar, Zwinger or Lopez, but a writer whose words were needed in their time.

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.