IT’S THE FOURTH of July and all the hillsides in my Northern California town are bleached blond. The landscape crunches, hisses, every bit of moisture long drained away.

I step outside on this Independence Day morning and my daughter toddles after me. She stays on the porch while I walk into the yard and pick up a garden hose. I aim the nozzle at the base of a sagebrush, but the water finds instead the skin of a rattlesnake basking in the morning sun.

I hadn’t noticed the animal lying motionless among the woodchips, my bare foot inches from her body. At the sensation of water on her back, or perhaps at the vibration of my footsteps or the scent of my toes, the snake leaps forward into the shadows beneath my porch. For an instant I feel her tail, firm and meaty and cool, slide across my foot. Her skin on my skin.

A second later, the snake’s rattle erupts like a crack of thunder and I jump back, dropping the hose to the ground. My daughter looks up at me from the porch, wide-eyed. I hop the step and lift her into my arms. Beneath us, the snake coils against a pier block. Sunlight spills through gaps between deck boards, striping her diamond-patterned body gold. Her rattle, vibrating so fast, is only a blur, but the sound is deafening. Adrenaline has set my limbs shaking, and for a moment I feel as if my own body is the drum, the rattle hammering inside me.

At last the snake’s tail slows, then putters out, and my own heartbeat calms. It is, once again, a still summer morning. Only the soft purr of the garden hose, spraying unmanned into the air, breaks the quiet.

MY ENCOUNTER with the snake that morning was not my first, though it was likely my closest. I grew up here in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, where northern Pacific rattlesnakes are part of the landscape— my high school mascot was the diamondback—and each year I expect to come across a few snakes. But the year I nearly stepped on that rattlesnake, I encountered so many I lost count. The first lay stretched atop my driveway, soaking

up the asphalt’s heat. The next, a young snake no thicker around than a pencil, coiled in a plant pot. Another slid across the dirt path to my house. Another rattled beneath a boulder atop which perched my cat, licking her lips.

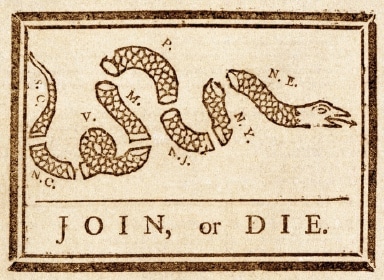

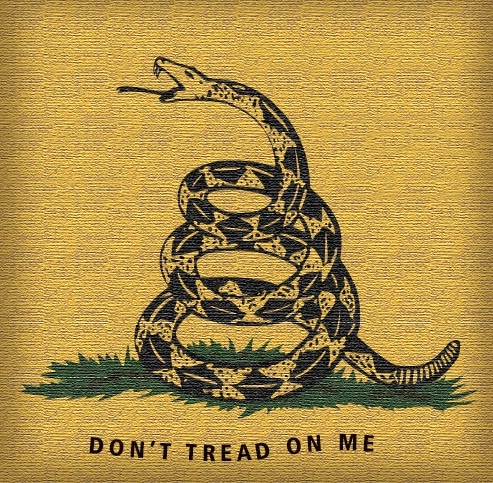

As the 2016 presidential campaigns heated up that same year, I noticed another kind of snake showing up regularly around town. This snake, also a rattler, appeared on bright yellow flags hung in front yards, on bumper stickers and hats. With her jaw opened wide and her daggerlike fangs deployed, she coiled above the words “Don’t Tread on Me.” Called the Gadsden flag, this image dates back to the Revolutionary War, when Christopher Gadsden designed it as a pro-independence symbol. At the time, the rattler was a prominent emblem of American national identity. A famous political cartoon drawn by Benjamin Franklin to urge colonial unity reads “Join, or Die” and depicts a rattlesnake broken into thirteen segments. Several dollar bills included the snake, as did the mastheads of early American newspapers. The rattlesnake was even a popular candidate for national animal.

I’d occasionally seen the Gadsden flag around town before, but that summer I saw it nearly every day. The vitriol of the presidential campaigns seemed to give people new impetus to stake claims on who they were and what they, and, in turn, their country, stood for. Stances were solidified, flags were hung, and the snake image proliferated. As the election neared, I saw live rattlers everywhere. Even where there were no snakes, I saw them— a stick outside my front door, a curl of rope on the road, a stray sock lying fox-stickered in the grass—until at last the ballot counts came in, the shock settled, and the chill of winter drove the snakes into hibernation.

THE FOLLOWING SPRING — the start of snake season, when the sound of a sprinkler coming on makes you jump — a friend told me of a phenomenon she’d recently read about: rattlesnakes losing their rattles. The story went something like this: Traditionally, rattlesnakes rattled to deter predators. The sound warned the other animal of the danger present in the snake’s venomous bite and deterred an attack. But, due to humans encroaching on snake habitat, the rattles were now producing the opposite effect. When a snake rattles around a human, the human retrieves a gun or the pointed end of a shovel instead of taking heed of the warning and retreating. The silent snake survives while the loud one is killed, resulting in an evolutionary adaptation leading to rattlesnakes who don’t use their rattles and snakes who’ve lost them altogether.

News of these rattleless rattlesnakes spread, and the more I heard the story, the more it began to sound familiar, to echo another narrative spreading quickly that spring: of America losing its American-ness. An Associated Press–NORC poll published in March 2017 found that seven out of ten Americans, from both sides of the political divide, believed America was losing its national identity. This sentiment was palpable in my home county, one that had been fiercely divided down the middle by the election. At the time, I worked as a baker, selling bread at the local farmers’ market. My customers’ views spanned the political spectrum, and they offered a similar set of comments each week. “My neighbors won’t quit nagging me about my yard, telling me to clean up. I’ve lived here sixty years! Well, they can go on back to China if they don’t like it here,” one man said. “This town has become something else — whole damn country has.” Another customer informed me that our town’s vice mayor was seeking a city council vote to block California from becoming a sanctuary state. “Couldn’t believe it when I heard it,” the man said. “This! This is what our country has become? I thought this place was built by immigrants.”

If America was in fact losing its national identity, I wondered, what exactly was that identity? How might I locate it?

One afternoon I took a walk down the road from my house, and there on my neighbor’s barn flapped a freshly hung Gadsden flag. I looked at its snake: coiled body, protruding fangs, raised rattle. Was it true? Were rattlesnakes losing their rattles, their namesake trait? Was their very nature eroding? I tried to picture the snake without a rattle, tail ending instead in an abrupt stub. Would I recognize the animal? The question of identity seemed manageable in the context of the snake in a way that it wasn’t with regard to my country. Perhaps if I could get to the bottom of this rattleless rattlesnake conundrum — if I could better understand these creatures that had once been a founding symbol of America and still crawled through the grasses of my hometown— I could in turn understand something about the identity of my country.

It’s also important to realize that the real problem is not human nature, but what I think of as an inhuman system. The presidential campaigns seemed to give people new impetus to stake claims on who they were and what their country stood for.

ON A BREEZY April morning, I drive to the Effie Yeaw Nature Center, a one-hundred-acre preserve in east Sacramento, to meet Mike Cardwell, a biologist and rattlesnake expert. I’d read about Mike’s work studying snakes using radio telemetry and hoped he could answer some of my questions. When I arrive, Mike is waiting near the park entrance, dressed in camouflage gaiters and holding what looks like a television antenna. He shakes my hand warmly and explains how we’ll walk through the park to check on a few transmitter-bearing snakes. “Then we’ll head to the far side of the reserve to release her,” he says, patting the fanny pack around his waist. “Her?” I ask. Mike chuckles. He’s carrying a rattlesnake, he tells me— “Number 75.” He’d caught the snake the prior morning and implanted a transmitter in her abdomen; today he plans to return her home. I assume the snake is anesthetized but Mike shakes his head, visibly horrified at this idea. “I keep a snake under anesthesia only as long as absolutely necessary for the surgery — twenty minutes, maybe. But don’t worry,” he adds, “she’s in a cloth bag.” I look back at the fanny pack, unsure how exactly a cloth bag provides much reassurance. But Mike pulls on a baseball hat and starts out into the park.

The land is mostly flat, thick with knee-high green grass. Swallowtails linger atop the blooms of milk thistle; a jackrabbit darts across our path. Distant weed whackers hum amid the flutter of birdsong. In his fifty-acre study area, Mike tells me, there are approximately one hundred adult rattlesnakes. I scan the open meadow and oak woodland within my view — parents push strollers, runners pass, a train of kids with tiny backpacks follows a teacher—and imagine the many rattlesnakes that share this space, curled beneath logs or slinking through the grass. Mike leads us along a dirt trail, waving his receiver about until it begins to beep, then detours into the grass. The first snake we find is sunbathing atop a rise; Mike gets a good look at her, but I catch only a flicker of her body before she disappears. Mike tunes his receiver to a new frequency and we move on in search of the next snake.

As we walk, Mike points out places he knows to be favorites of the snakes: a log he calls “The Community Center,” another he’s deemed “Love Boat.” When we reach Love Boat I expect to see a big, picturesque log, a snake strutting across the top, but the log is grayed and rotting into the ground. Mike peels back blades of grass with a stick and peers between them. This morning, Love Boat is vacant. We pass a popular wintering site and Mike tells me he’s been surprised to find the snakes at Effie Yeaw hibernating in groups. While this behavior is common in the eastern US, where severe winters make suitable dens few and far between, it’s unusual in regions with mild climates like Sacramento. In the absence of an environmental explanation, Mike believes these snakes are wintering together due to family bonds.

Near the back of the park, we stop in a pocket of shade, and Mike unzips his fanny pack. Careful to stand in the exact place where he caught the snake the prior day, he pulls out what looks like nothing more than a white pillowcase. The curves of a snake’s body push against the fabric. Mike sets the bag in the grass, then tugs at the closed end to coax the snake toward the opening. Slowly, she crawls out. Once in the grass, she lifts her head and swings it quickly around to face us. I instinctively step back, but Mike remains still. The snake’s skin shines softly in the afternoon light, and I admire her dark diamonds. Like our fingerprints, no two rattlesnakes’ skin patterns are alike. The snake flicks her tongue and slithers toward us. I take another step back. Then she stops, curls her neck to face the opposite direction, and slides swiftly out of sight.

IN 1775, Benjamin Franklin, using the pseudonym “An American Guesser,” wrote of the rattlesnake:

[T]he weapons with which nature has furnished her, she conceals in the roof of her mouth, so that . . . she appears to be a most defenseless animal; and even when those weapons are shown and extended for her defense, they appear weak and contemptible; but their wounds, however small, are decisive and fatal. Conscious of this, she never wounds ’till she has generously given notice, even to her enemy, and cautioned him against the danger of treading on her. Was I wrong, Sir, in thinking this a strong picture of the temper and conduct of America?

Since Franklin wrote these words, over two centuries ago, our knowledge of rattlesnakes has grown. Contrary to Franklin’s belief, it’s now well established that rattlesnake venoms have not, in fact, evolved for the purpose of defense. The initial bite from a rattlesnake is virtually painless, and the venom does not act quickly enough to deter a predator from continuing to pursue the snake. Rather than for defense, venoms are designed to kill prey.

Here in Northern California, rattlesnake venom is evolved to counter the defenses of one of the snake’s main food sources: the California ground squirrel. These squirrels carry antivenom in their blood that, if effectively matched to the snake’s venom, will render the squirrel immune to the effects of a bite. The two species are locked in coevolution: each generation of snake equipped with a venom cocktail more potent to the squirrel, and each generation of squirrel better matched to resist the venom.

Because rattlesnake venoms are adapted to suit local predation needs, they are among the most complex and variable natural toxins, differing between species, populations, and individuals. Some bites cause blood to coagulate, while others impede coagulation. Some cause flaccid paralysis; others cause spasms. Some have analgesic properties.

The word venom comes from the Latin venēnum, defined as both a destructive poison and a magical potion. Rattlesnake venom can kill a person if a bite goes untreated, but it may also have the capacity to save lives. In a handful of labs around the country, rattlesnakes are “milked” for their venom, which is then collected and sold to pharmaceutical companies and university researchers who are using the venom to develop new therapeutic drugs. There are several medicines on the market derived from animal venom (including Integrilin, a bloodthinner; Byetta, an antidiabetic; and Prialt, an analgesic), with many more under development.

While some of Franklin’s observations remain accurate today— fangs are hidden, wounds are small and often fatal — under the scrutiny of recent research much of his depiction of the rattlesnake’s nature fails to hold up. In fact, the more we learn about these animals, the more slippery their nature seems to become, the more difficult to catch hold of at all. Had Franklin understood rattlesnake venom’s poor suitability for defense, had he known of its multifaceted potential as both poison and medicine or of its ever-changing constitution, I wonder: Would he have found the rattlesnake to be less emblematic of America? And what might he make of the news that some rattlesnakes have ceased to “give notice”?

A FEW WEEKS LATER, I arrive at the community room of the Auburn small plane airport where Mike is giving a presentation called “Living in Rattlesnake Country.” The event is a fundraiser for the local wildlife rescue organization, and I’m surprised to find the room packed despite the perfect spring weather. Mike begins by discussing the behavior and biology of rattlesnakes. He shows photos of just-born snakes, snakes swallowing prey, snakes mating. He shows a photo of a shed snakeskin, fully intact and lace-thin, and explains how, because the outer layer of a snake’s skin doesn’t grow, snakes must periodically shed this “corneal” layer. Each time a rattlesnake sheds, a new segment of her rattle is formed.

“I shed my skin, too,” a woman in front of me whispers to her friend with a giggle, pulling up her sleeve to display a sunburned forearm. “Just not all at once.” I look back up at the photo of the snakeskin. It’s true, what the woman said. In fact, the skin we see today will be replaced within the month. But unlike these snakes, we’ve no rattles to remind us just how many skins we’ve outgrown, no record of our own constant reinvention. Instead, we are encased anew without ever noticing that we’ve changed.

Halfway through the talk, we break for lunch. When everyone returns to the stuffy room, a photo of an inflamed shin, blackened and hugely swollen, shines from the projector. For the remainder of the day, Mike announces, we’ll turn our attention to snakebites. Now it becomes clear why most attendants are here today: they want to know how to not get bit.

Every year there are around eight thousand reported venomous snakebites in the US, nearly all from rattlesnakes. Of those, an average of five result in death. Nearly all of these bites are caused by one of two high-risk behaviors: intentionally bothering a snake or putting unprotected hands or feet where you can’t see them. If a person doesn’t engage in either of these activities, she’ll have almost no chance of being bit.

By this point in the presentation, we’ve heard several times that rattlesnakes are not at all aggressive, that they will only bite a person as a last resort. But the truth doesn’t seem quite able to counter the fear. “How fast would I need to be to outrun one?” someone asks. “If I see a rattlesnake while I’m hiking, would bear spray work against it?” queries another. If Mike is irritated by the persistence of these questions, he doesn’t let on. “You could try bear spray,” he answers patiently, “but snakes have skin covering their eyes, so it probably won’t bother them. An easier way to avoid a bite would be to simply walk around the snake.”

Someone asks Mike if he knows where all these myths, such as snakes leaping twenty feet to attack or chasing down trail runners, began. Mike sighs. “Imagine you’re at a party. In one corner of the room is a guy telling a story of the snake that chased him up a tree or followed him to his car and bit his tires until he drove off.” In the other corner, Mike asks us to imagine, is you. You’re explaining how this can’t be true based on documented snake behavior. “Who has the crowd?” he asks.

A man in the audience raises his hand and asks the question everyone’s been waiting for. “What if I see one in my yard? I’ve got dogs and horses, can’t have a snake just hangin’ around.” A rumble of “That’s what I wanted to ask” and “Me, too” passes through the room. Mike takes his time answering, as if he’s an athlete and this is the feat he’s long been training for.

“Replace dogs with little kids, ” he says. “It’s a concern many of us living in rattlesnake country share.” Speaking slowly, he continues. “There are two options in this situation: The first is to kill the snake. The second is to leave it alone.” To my surprise, Mike details exactly how to kill the snake: Use a shovel to swiftly decapitate the animal. Don’t use a gun. Don’t touch the severed head for at least an hour because it will still bite as a nervous reflex.

After offering this option, he adds an addendum. The room is quiet, attendants rapt. “There are two things to keep in mind if you decide to kill the snake.” First, the overwhelming majority of bites occur when people are messing with a snake, as in trying to kill one. Second, if you encounter one snake, there are certainly many more in the area. By killing the snake, you will not alleviate yourself, your pets, or your children of the possibility of being bitten. But you may cultivate a false sense of security, and this, in fact, is very dangerous.

The best way to avoid a bite by a rattlesnake is to pay attention: watch where you step or place your hands, look carefully when grabbing a log from a woodpile or walking in high grass, and remain aware of the possibility of a snake. If you do these things, you will almost certainly not be bit.

This, it seems, is not quite the answer most people were hoping for. A deflated “hmm” passes through the room. Pencils hover over notebooks, still waiting for the tidy tidbit to write down. The solution is not one that can be purchased, or installed, or easily checked off a list. Instead, it is a call to change the way we view our surroundings, to accept that our environments are shared spaces, and to attend to the daily work of paying close attention.

AT THE FRONT of the room sits a plastic bucket. Mike opens the lid and reaches inside with a hooked stick. Slowly, he lifts out a snake and lowers her onto the table. She lies motionless for a moment, and people gather up close with their phones out, snapping photos. Mike begins to coax the snake toward the opening of a clear plastic tube just wider than the girth of her body. She resists, dodging the opening and rattling loudly. People exchange glances, shift weight. But Mike is as calm as ever, guiding her toward the tube with his hooked stick as if poking food around a dinner plate, until at last she crawls inside.

Now the snake must be anesthetized so that Mike can perform an exam. He attaches a bottle of sevoflurane to the plastic tube, then squeezes the bottle. Vapor enters the enclosure. Minutes pass and the snake’s movements slow until, when Mike gently turns her upside down, she no longer attempts to right herself. He slides her out of the tube and she remains limp as a banana peel as he straightens her body against a ruler. When he leans close to her face there is an audible sucking in of breath, as if we can’t quite believe the snake won’t wake.

Near the end of the exam, Mike rolls the snake onto her side and points to a place near the center of her body. Here, he tells us, if we look closely, we’ll see the beating of her heart. I lean in, squint. Beneath the pale scales of her underside is the rhythmic twitch of a heartbeat. “Rattlesnakes might be a different shape than us, different than most of the animals we’re familiar with,” Mike says, “but when you look close, you’ll see we all have the same crucial parts.”

Lastly, Mike rests the snake’s chin in his fingers and gently opens her mouth. I look for two sharp fangs curving down, like those on the Gadsden flag, but instead I see only smooth flesh like that of my own gums. When not in use, a rattlesnake’s fangs fold up against the roof of her mouth to prevent her from biting herself, Mike explains. He pulls them gently down with a probe, and, one by one, we all file past to get a close look. Because rattlesnakes have no eyelids, the snake’s eyes are wide open as I put my own face close to hers. Her head is much smaller than I’d imagined — smaller than the pad of Mike’s thumb. The inside of her mouth is the pearly pink of the tender new skin that emerges from beneath a scab. Each of her fangs is no bigger than a fingernail clipping.

We return to our seats to wait for the snake to regain consciousness. A woman raises her hand. “Can a rattlesnake sense my fear?” A chuckle passes through the room. Mike grins but speaks in a serious tone. “My initial reaction to that question would’ve been no,” he says, the snake’s head still resting in his palm. “But I also would’ve never believed that a rattlesnake could rearrange blades of grass to better ambush a squirrel, or form familial bonds. And we now have convincing evidence that both these behaviors do occur. So, maybe.”

The snake lifts her head, curls her neck around to look at Mike. Her movements are eerily slow, and Mike slides her back into the bucket while she’s still lethargic, then asks for any last questions.

A man in the back row raises his hand to ask the question that had started me on this whole rattlesnake foray. “I’ve heard some rattlesnakes are no longer rattling because so many are being killed by people,” the man says. “Is that happening here?”

Mike’s answer: We don’t know. But he doubts it.

It’s possible that this could happen. After all, rattlesnakes have not always had rattles. Many scientists hypothesize they were once merely snakes who rapidly shook their tails when threatened, and, over time, this behavior led to the evolution of rattles. So it’s possible that the rattles could leave the snakes in a similar manner. But it’s very unlikely this is happening. In order for a trait to become genetically imprinted, a significant potion of the population must be impacted. “When we consider ow many rattlesnakes never encounter a human— the majority of snakes— it’s hard to imagine people have made enough impact to result in a genetic change like this,” Mike says.

He does, however, have an idea of how this rumor may have started. Rattlesnake behavior differs widely from place to place, as the animals adapt to the conditions of local environment In the desert landscapes of Southern California, for example he environment offers snakes few places to hide from predators. Therefore, they rattle fervently and often when threatened. In the foothills of Northern California, however, there are so many places for snakes to conceal themselves that the animals often opt to hide for defense, rattling only as a last resort.

A person accustomed to the behavior of snakes in South California might notice the reluctance of snakes in North California to rattle and find this odd. He might even conclude that the essential nature of the rattlesnake is eroding, w in fact he’s simply noticed a diversity of behavior that has existed all along — a testament to the fact that the nature of rattlesnakes is not so essential at all, but instead varies from species to species, population to population, snake to snake, and year to year.

The crowd nods, perhaps a little disappointed. “Makes sense,” the guy next to me mumbles softly. There are no more questions, and everyone files out of the room into the clear spring afternoon.

THE NEXT TIME I walk around my neighborhood, I pause again at the house a few doors down that flies the Gadsden flag. A breeze ripples the fabric and with each fold the snake’s rattle disappears, then reappears. I think again of the nature of my country. Perhaps my mind too easily draws parallels, eager to take cheap comfort at a time when any comfort is hard to find. What is true for snakes is, of course, not necessarily true for a nation. But if nothing else, the story of rattlesnakes reminds me that identity — that of a reptile or that of a country — is not a fundamental or static thing, not something that can be lost but something that exists in a constant state of motion, of plurality, and of possibility. And so perhaps, also like rattlesnakes, what makes us who we are is not simply our origins but how we behave in our current environments, how we adapt to changing surroundings, and how we learn to live alongside one another.

When I see a real rattlesnake again, it’s a late summer afternoon, and she’s curled against a tree behind my house. Sunlight filters through the canopy of oaks and dapples her skin. I watch from a few yards away. Her tongue flicks, face lifts. And though I cannot see them, I know there are fangs folded neatly against the roof of her mouth. There are heat-sensing pits on her face that are quite possibly translating my body heat into an image she is now looking at. Hidden inside her head are glands filled with venom, and within that venom are molecules that might contain the ability to both destroy flesh and treat cancer. And somewhere near the center of her body, there is a peanut-sized heart, pumping.

I leave the snake where she is. When I look for her later, she’s gone. O

Comments

An incredible piece – for all the right reasons.

Great post!

Wow. Love this essay. As stated above, for all the right reasons.: nformative, interesting, and beautifully written.

Ach, that last paragraph. Beatiful.

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.