PAUL KOZAK STANDS at a microphone in East Boston High School’s auditorium on an early February evening. He holds a dead fish in his hand, visible from around the room. One can imagine its lolling eye, a scent of decay held at bay by its plastic bag. The room is quiet, save the occasional furtive whisper. The suited officials on stage listen to Mr. Kozak, eyes trained on the fish. He is protesting a tilted public process and the inability of local residents to influence it.

Mr. Kozak asks members of the Massachusetts Energy Facilities Siting Board to reconsider siting a high-voltage electrical substation not far from his own home in East Boston’s Eagle Hill neighborhood, next to Chelsea Creek. Behind him are residents and supporters who share his concerns. They hold up neon poster board signs and wear matching T-shirts designed by GreenRoots, an environmental justice group that has organized many of those present. Employees of Eversource, the electric utility petitioning to build the substation, line the edges of the room. Eversource claims that the project is necessary to address the area’s growing electricity demand, and its proposed placement and design would minimize the cost of construction, which would be passed on to its customers. Though, pending approval, they plan to build the project half a mile from here, this is the first time — February 5, 2019 — the board and Eversource have held a public meeting in East Boston.

Kozak addresses the board: “I speak here as a resident of East Boston. I am probably the third closest house to the new site change, approximately sixty yards I would guess from the site. I have three children: ages six, four, and two. I speak for them as well.” His tone is measured, in an attempt to temper the palpable anger in the room.

Kozak is one of dozens to provide public comment this day. Elena Letona, a native of El Salvador and director of Neighbor to Neighbor, an immigrant rights organization, provides her testimony also. Her voice is full and commanding: “Do any of you live in East Boston or Chelsea? I am guessing not. We have already heard plenty of how this region bears the burden of environmental threats and consequences for serving many of the neighborhoods outside of East Boston.” She takes care to pause, holding on to the silence between her statements, “Maybe yours.”

The proposed substation site faces Chelsea Creek, which sustains the kinds of industrial activity necessary for the rest of Boston and the region. The creek divides the city of Chelsea from East Boston; its corpus is riddled with ailments. Fat circular drums and drifting barges have left pollutants on its shining surface. Tightly sewn rows of houses border the freeway, which separates them from water. East Boston’s industrial burdens are part of lengthy New England supply chains: the heating oil, salt, and jet fuel that the rest of the region depends on are located here. Residents at the substation hearing are quick to point this out: the bewildering imposition of infrastructure on their communities has been par for the course, forcing them to chide public officials and business leaders in high school auditoriums, city halls, and community centers for decades. These fights extend as far back as the expansion of Logan Airport in the 1960s. Within them are the heady trade-offs between economic development, parkland, pollution, noise, health, and quality of life.

Fran Ippolito Riley, an activist who has lived in East Boston for seventy-six years, makes her statement. She lectures the officials elevated on the stage in front of her like a strict mother, one that has just caught her child misbehaving. “You’re going to leave here tonight and realize . . . when we speak of the airport and the tunnels, and everything else, you do not understand. You don’t live here. This electrical substation: that’s the ugliest thing I’ve seen yet on the screen. Putting it there, it’s like putting liverwurst in an Italian cannoli.”

The audience laughs and claps, though the board’s secretary previously gave explicit instructions to hold applause between statements.

Riley ends her testimony with a declaration: “Guess what? It’s not happening.”

This scene is representative of local politics in East Boston. The future of a piece of land is decided via the heady technical analysis of a builder, often a developer or corporate interest. The public is left to respond with theatrics to convince officials to listen to them. At tonight’s hearing, residents share concerns in acerbic detail, fitting their opinions into the convoluted processes of siting energy infrastructure. But the siting board had already approved the project in November 2017, after a long legal battle with a nearby fish-processing plant, Channel Fish. Louis Silvestro, the owner of the plant, believed the substation would have harmful effects on his equipment. In 2016, he hired experts and lawyers to intervene in the case. Following his formal intervention, the utility agreed to move the project 190 feet farther away from the property, which is 190 feet closer to the American Legion playground. The new proposed site also falls next to the Condor Street Urban Wild, a remediated piece of city-owned land that community activists helped transform into a green space. Changing the site’s location reopened the state’s evaluation process.

Industry has a long history here, and the area’s port designation allows it to continue. Enormous white cylinders dominate the landscape. Operated by Sunoco, the tanks hold all of Logan Airport’s jet fuel. Industrial pollutants like PCBs have settled in the river bottom. These contaminants travel up riverine food chains, eventually lodging as fleshy deposits in the river’s fish. Petroleum hydrocarbons, the chemical remnants of oil spills, also flow through the water.

Twenty years ago, a tugboat accidentally collided with an enormous tanker it was meant to be guiding, boring a hole into its hull. Around fifty-nine thousand gallons of fuel oil oozed out into the creek, outdoing the last major spill, which took place six years prior. On one end of Chelsea Creek is an Exxon Mobil oil terminal, which spilled another fifteen thousand gallons of oil into the creek in 2006, seeping black tar down into the waters. Negligence defines these incidents, and residents have had no choice but to bear its consequences. Yet, over decades, neighborhood activists have also helped to clean up this area and stop the placement of additional dangerous infrastructure.

This waterway holds Boston’s industrial past and present, far removed from the pristine running paths along the Charles River or the condominiums that have come to line the city’s southern harbor. Its qualities are nearly bygone in the context of Boston’s cosmopolitan future. As Boston has followed the trajectory of postindustrial cities around the globe, its economic production is no longer material in nature. Chelsea Creek is a place demonstrative of the hidden burdens required for this urban lifestyle, the lionized heart of the postindustrial city.

Boston Harbor has always been a working port. In East Boston it is dominated by industry.

Residents have filled several rows at the high school’s auditorium, and a long line of them are waiting to speak. Tina Kelly, the former president of this neighborhood’s civic association, describes how the current scenario is a familiar one: “I’ve had so many meetings in this very hall, fighting and fighting. It gets really tiring. I’m a mom. I’m trying to raise my kids.” Then Kelly refers to the seizure of parkland by the Massachusetts Port Authority, the operator of Logan Airport. “I don’t know if any of you know the history of this community,” she says. “They continually take and take and take, and they don’t listen to any of us.” Anger and frustration at public process runs deep here, palpable in the room.

“You’ve heard a lot tonight,” says Kozak, “sometimes we need the visual. So, I brought with me a dead fish. Eversource has conceded that the high voltage impacts fish. But the next logical step is to move the site closer to a playground?”

East Boston, more affectionately named “Eastie,” is a peninsula that juts outward from Greater Boston. Its land is embraced by blue swells of the harbor, which ebb and flow against its shorelines. It is cut with jagged edges of piers and docks, skirted by heavy industry. From the south, the Ted Williams Tunnel runs submerged under Boston Harbor, through to Logan Airport. Around its southern edge, ships move into the harbor, dwarfed by a hastily drawn Seaport skyline and downtown Boston’s looming towers. To the north are the waters of Chelsea Creek with its hulking barges and clustered oil drums. At Beachmont, a strip of land connects East Boston to the neighboring North Shore region. A salt marsh here periodically flows with the ocean’s briny water.

The peninsula is precarious in its watery isolation, but its communities are close-knit, bound together by water and rings of infrastructure that run alongside it. Eastie’s residents most commonly live in triple-decker homes, colored in desaturated pastels. The Maverick Street subway station is crowded with urban bustle and communal life; Spanish language advertisements are splashed across the faces of its markets, laundromats, restaurants, and bakeries. East Boston’s far reaches of Orient Heights are quieter, with the muted coastal tones of a New England summer town. Eagle Hill is mostly residential, leading up to the creek. Occasionally apartments seem to lean on body shop garages and corner markets.

The peninsula is precarious in its watery isolation, but its communities are close-knit, bound together by water and rings of infrastructure that run alongside it.

In decades past, East Boston was an Irish and Italian immigrant enclave. Eastie is an arrival point, often the first step onto American land for families who settle here for generations. Today, the Maverick rapid transit station stop hosts bright red newspaper boxes selling El Mundo and El Planeta, two of Greater Boston’s Spanish-language papers. Grocery stores advertise Colombian, Salvadoran, and other Latin American products. The 1990s brought an influx of immigrants from Latin America; today, half of East Boston’s forty-five thousand residents are foreign born. Eastie’s salty port has welcomed newcomers fleeing persecution, war, violence, or poverty. These mixed legacies are visible in the streets and storefronts, and also present at the hearing at East Boston High School.

At the hearing, other residents take their turn in Spanish, in solidarity with the Latino people left out of the process. During a decisive November 2017 hearing, the board did not provide two-way interpretation services in Spanish or Portuguese, spoken by Eastie’s Brazilian immigrants, or, for that matter, any other language. Although siting board members were able to hear the English interpretation of Spanish testimony from community members, community members were not provided with an interpretation of the meeting’s proceedings, which were in English. This remains a bitter insult in the minds of residents, who waited in a room for four hours, hearing officials and staff speak incomprehensibly about the future of land that sits so close to their homes. Although interpretation services are provided at this February hearing, Indira Garmenia, a forceful organizer with GreenRoots, provides her comment in Spanish and reminds the board: “In November 2017, you, the same board that’s here today, met regarding this project. The only time there were words in Spanish was when I gave my testimony. Clearly that was a violation of our civil rights.”

At the end of the hearing, residents and organizers chant, “Cuando luchamos, ganamos!” into the emptying auditorium. When we fight, we win.

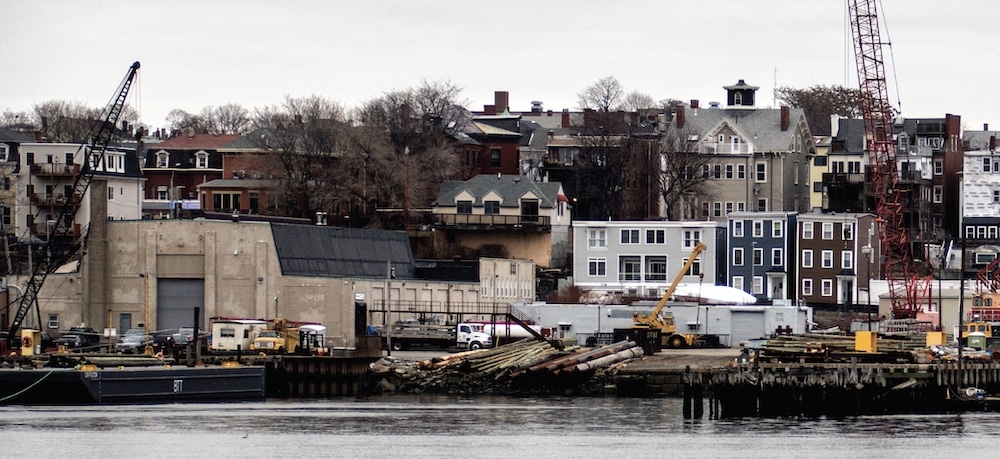

Houses form a backdrop to freight traffic in Boston Harbor.

Winning this fight would be a small demonstration of autonomy over Chelsea Creek’s waterfront, which is embattled by a number of interests. A month after the hearing, John Walkey, a resident of East Boston and the waterfront initiative’s coordinator for GreenRoots, describes the ways in which community groups have worked to protect Chelsea and East Boston from industries around the creek, while also restoring access to the water. The GreenRoots office sits on the opposite side of the creek as the substation site, and is situated in neighboring Chelsea. From its windows, one can see ships passing by. In the aughts, GreenRoots organized residents and stopped siting and construction of a diesel-burning power plant very close to an elementary school in Chelsea.

Walkey explains how in Chelsea, “You’ve got three sides of the city surrounded by water, and yet nobody had access to it.” Over the years, East Boston advocates have fought for waterfront open space projects. One organization, Harborkeepers, seeks to redefine East Boston as a waterfront community. Harborkeepers’ volunteers have hauled up trash from the sand on Boston’s windiest days, collecting chip bags, crushed beer cans, and torn plastic bags. The organization’s office overlooks the potential future site of Eversource’s substation. The walls are covered with maps of East Boston, satellite imagery of all the jagged landforms and architectures.

In this space, Heather O’Brien, the organization’s former community planner, offers insight about her community. She’s been living in the Orient Heights neighborhood for nearly six years. She and the current director, Magdalena Ayed, and other neighborhood activists have organized community cleanups, coordinated emergency preparedness trainings, and taught environmental education to Eastie children. O’Brien makes it plain that the waterfront in East Boston is a site of symbolic and literal contest in these neighborhoods. Wedged between the airport, industrial contamination, and now luxury development, East Bostonians might consider themselves a community that has a relationship with the harbor, ocean, and creek. East Boston’s isolation has also led O’Brien and others to think about what unequal futures might materialize in case of an emergency, especially for its linguistically isolated populations.

“We had a community meeting a couple years ago about emergency preparedness. It was in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, and we were thinking if winds and currents had been a teeny tiny different, it could have been us. East Boston is really cut off from everything. And we have a lot of people who don’t have access to a car who would have nowhere to go.”

An emergency situation is exactly what residents of Eagle Hill fear. Flooding concerns most residents who publicly oppose the Eversource substation. The utility claims it designed its substation to several standard flood projections, including FEMA’s five-hundred-year storm levels, and in consideration of the city’s forward-looking projection for 2070. However, given the predictions for sea level rise in East Boston, residents are re-evaluating the possibilities for its waterfront, having grown wary of new development of any kind.

Dr. Marcos Luna, an Eagle Hill resident and geography professor at Salem State University, testified that Eversource has failed to demonstrate that the substation can withstand flooding, stating that the flood analysis by Eversource’s consultant “had nothing that shows the projections for the flood extent in the future.” He produced his own maps, which GreenRoots distributed to residents in opposition to the project. He also argued that Eversource did not use the worst-case figures in its choice of elevation. Dr. Luna found the substation to be within, not outside, the city’s projections for sea level rise between 2050 and 2070, as Eversource suggests. Additionally, there are no legal impediments to the utility leaving the structure in place for the years following 2070, even if flooding worsens. In the case of a storm like Superstorm Sandy, the substation is in a hurricane evacuation zone.

Instead of an electrical substation, Dr. Luna would like to see something that can be flooded safely. “Something,” he says, “that assists the natural processes, allows the wetlands to naturally recover.” Residents in opposition to the substation have expressed interest in a green space, one that could handle a creek swollen with pollutants, rain, and high tide. With so much of Eastie exposed to water, residents wonder what would happen to them living near this facility during the next big storm.

A cluster of enormous fuel tanks looms over Chelsea Street.

Parts of East Boston smell like salt and sea air. Occasionally, a gull lands in Maverick Square, looking for shoreline in the bustle of commuters leaving the train station. In many parts of Eastie, water is the inconstant boundary between new construction and old industry. During storms, water floods basements and pools upward into grocery store parking lots and the elbows of streets to find its level. The Boston Harbor has always been a working port, where lobstermen and longshoremen sustained their livelihoods. But today, real estate developers dream of water taxi routes connecting islands of luxury housing between East Boston and the Seaport. Beautiful harbor walks lit with golden light and briny shoreline live in the renderings of these new buildings, which bear names echoing maritime pasts. Though the city needs new housing, most of the units rent at luxury prices. Large apartment units are also scarce, putting even more pressure on families trying to make a life here.

In the northern part of East Boston, HYM Properties, a multimillion-dollar developer, is in the process of developing Suffolk Downs, an old horse racetrack near Revere and the Belle Isle Marsh. The 161-acre property is one of the biggest in Greater Boston, a smorgasbord of all kinds of new amenities that come to characterize Bostonian development in the 2010s. The vision is gargantuan: HYM envisions adding ten thousand new units, no small ambition, relative to East Boston’s forty-five thousand residents.

The newly built and nautically derived Clippership Wharf and Portside at East Pier are located on the western side of the peninsula, close to Maverick Square, and have brought in the next wave of wealthy young professionals. There is no playground on the property, but there is a dog park, a telling sign of whom this place will belong to. The architecture overwhelms, and the facades seem indistinguishable from a college dormitory: not gray and geometric but oversaturated red and orange.

Saturday at Maverick Square in East Boston.

These structures aggressively crowd the harbor, except for the tiny strip of East Pier Drive. Though technically anyone can access this part of the waterfront, the complexes are unwelcoming. Their apartment buildings loom over a pedestrian in the way of a fortress. Yet in 2050, parts of Portside and Clippership Wharf will be susceptible to storm surges and flooding, per projections by the city. Clippership’s developers created a tideland park on its harbor-facing side to protect the building and its tenants from rising waters. Parts of the development will be raised upward of twenty-five feet to allow for intentional flooding; architects plan for water to flow through the property’s designed retention area. Where there are resources, shoreline protection follows easily.

Waterfronts are extractive places. Those with capital have generated more of it through industrial and manufacturing activity, and in today’s economy, waterfront real estate. Community members are often caught between these two poles. Projects like the substation and luxury apartment buildings turn the waterfront into a site of constant contestation, with outside forces imposing projects on long-standing residents.

Throughout 2019, GreenRoots served as intervenors in the substation case. Hearings dragged on in nondescript rooms on sweltering summer days. Interpretation services improved, but only marginally. Allies and residents alike appeared again and again to voice their anger at the project, which has become a lightning rod for climate and environmental justice in Greater Boston.

In early March 2020, Massachusetts postponed the project’s final hearing because of COVID-19. The pandemic has both halted the public comment process surrounding the project and also frozen much of the industrial activity that lines the creek and both East Boston and Chelsea. Once again, Eastie has become a microcosm for the stark inequalities in American life. Infection rates in Chelsea are the highest in the state, and East Boston’s infection rate is higher than the city average. A professional class of knowledge workers stays home, ordering deliveries and meals, while a working class is exposed to the virus as they deliver goods, stock shelves, and serve meals. When the transit authority reduced service in Greater Boston, East Boston and Chelsea’s workers boarded crowded trains and buses, unable to heed any guidance on social distancing without losing their livelihoods. The authority later added service back to alleviate the crowding, but not without some measure of public outrage, which followed an all-too-familiar pattern.

The same organizers who packed the hearing rooms for the substation project did their best to keep their community safe, despite a government that continues to imperil them. As the pandemic continues to expose the already deep disparities in Boston, perhaps new forms of governance that include larger social safety nets with community control may be made possible. Pollution and pathogens follow historical pathways, sieves of long-standing inequalities; their consequences trace the structures already in place. What follows on a warming planet with rising waters is uncertain. What is essential is the retooling of systems that enable these injustices. O

Comments

This is an important and powerful article. Any plans to translate it into Spanish so the many people in East Boston who do have English as their native language? Many thanks.

Great article. I will return later to finish the rest, but I must say, I appreciate the narrative writing in the article. I don’t live in Boston, but I could picture this location and what was going on.

Please Note: Before submitting, copy your comment to your clipboard, be sure every required field is filled out, and only then submit.