Together Apart is a new Orion web series of letters from isolation. Every week under lockdown, we eavesdrop on curious pairs of authors, scientists, and artists, listening in on their emails, texts, and phone calls as they redefine their relationships from afar.

Our first installment was an email exchange between Amy Irvine and Pam Houston. The second, a phone call with Krista Tippett and Pádraig Ó Tuama.

Our third conversation is a series of emails between Pulitzer Prize finalist author William deBuys (A Great Aridness, The Last Unicorn, The Walk) and bestselling author and fly-fisherman David James Duncan (The Brothers K, The River Why, My Story as Told by Water).

April 8, 2020

Hello David,

I hope this finds you well and safely ensconced in your Lolo Creek world. No complaints down here in the Sangre de Cristo land, New Mexico. Spring is breaking out. Saw my first snake, lizard, butterfly, and flower blossom of the year all in the last two days, and the pastures are greening fast. Rivers are still low; the high country melt hasn’t begun.

Only a dozen or so cases of COVID-19 here in Taos County and no deaths so far, thank goodness, but it is plain that harder times are coming. Meanwhile, in the rest of the world, so much suffering, heroism, idiocy, fear, and toughness—the whole gamut of human behavior and circumstance seems to be on fast forward.

Around here, it feels like fire season, when everything local is okay but the land is dry and you can taste smoke in the air from big burns far away. This time, those burns wrap all the way around the planet.

How are you faring? Does the situation pull you away from your work or feed it? I am sure you’ve got plenty of friends and maybe kin in harm’s way. Fingers crossed for everyone we love.

Best,

Bill

April 8, 2020

Dear Bill,

Great to hear from you. I realized I’ve felt “together apart” with you ever since, and it’s past time we were conversing again.

Remember that day? A long hike into Idaho wilds up a high and pristine tributary of the Columbia/Snake as the Interior West’s wild salmon were being driven to extinction by a federal welfare program, in order to barge wheat down the river rather than run it by the adjacent railroad to the tune of 20,000 taxpayer dollars per barge.

Meanwhile, a starving orca mother named Tahlequah was about to give birth to an infant that died within hours, as all Salish Sea orca infants have been dying. And why? So their mothers can starve for lack of wild Idaho chinook slaughtered by eight dams, 450 miles of slackwater, and a wheat-barging scam that bilks struggling taxpayers while mega-corporations are taxed not at all.

But this orca mother did something preposterously out of touch with realpolitik, as I’m sure you know. For seventeen consecutive days Tahlequah carried her infant’s corpse over a thousand miles through her home waters. And, on the ninth day, when other orcas from her pod held the moldering baby so she could rest without it sinking, I drove into the same chinook spawning water you and I visited and checked every overlook and holding pool where I’d seen spawning spring and summer chinook for twenty-five years. I saw not a single salmon, Bill. Which was bad enough. And when I got home that evening I made a serious mistake: I listened to a NOAA recording of Tahlequah’s cries as she carried her disintegrating infant those thousand miles.

I have long known the cathartic power of great literary tragedy. But this was wildly more tragic and wildly less cathartic. The sound of a grief-smashed orca mother outstripping the work of every tragedian from the Greeks to Shakespeare—it shattered me. I could only stagger back to the creek and sob myself dry.

So how lucky we were, then, on our Idaho day, to hike into the heart of a wilderness afternoon turned glorious when a big hatch of mayflies appeared in shafts of sun over that salmonless stream. With the mayflies our conversation took flight. And we returned to Adrian’s and my place for a little single malt scotch and dinner, I still remember how good the talk was to day’s end. How good to be back in touch.

Change of key amid the current world chaos:

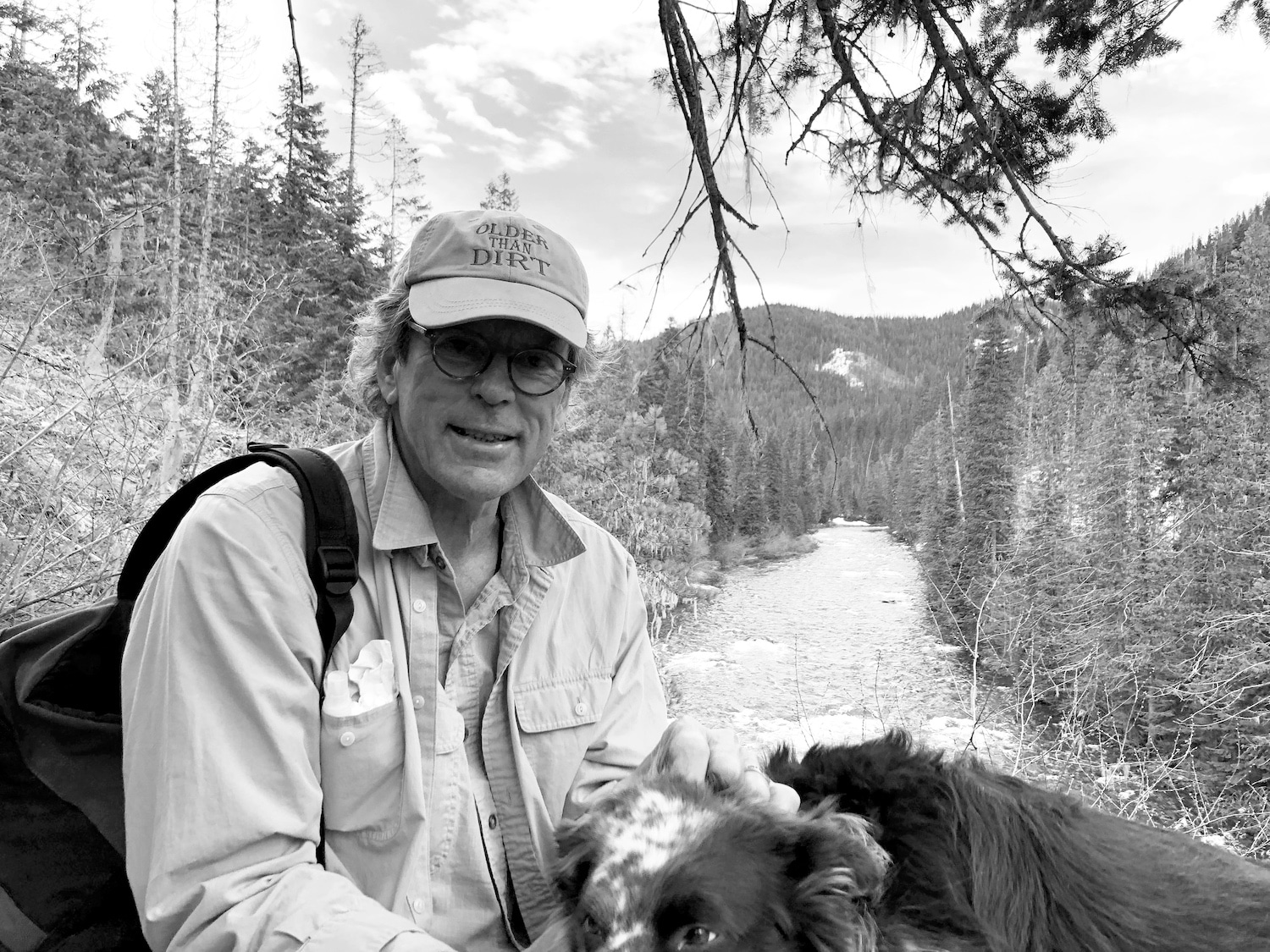

I saw photos of you teaching the Freeflow Institute floating Salmon River writers’ workshop. Now, I am not a covetous man, Bill. But on the website you are photographed wearing a ballcap with the words OLDER THAN DIRT on it, and a grin to match the words. On the off chance you’d consider parting with it, I covet that cap regardless of its current condition!

Wishing you impossibly good things in this dark yet fascinating time as so much hubris is going up in flames and industrial humanity’s undreamt-of fragility is laid bare.

Tahlequah, keep singing to us.

Be well, Bill.

David

April 10, 2020

Hermano David,

The OLDER THAN DIRT hat is on my head and it will be on its way to yours as soon as I can get over to the post office in Chamisal, where there is never a line. The hat was given to me by a crusty river guide and archeologist with whom I made several trips through Grand Canyon. I had admired it boat-to-boat, and on our last trip together he frisbeed it to me at the take-out. Now I am frisbeeing it to you. This hat needs a new good head, and the gift must always move.

Would have written sooner but got waylaid by ditch business. I hold elective office in our Acequia Association—which is worse than being elected dog catcher—and yesterday, after multiple repairs and delays, we finally opened the headgate of our much loved Acequia Abajo, it was my duty to “walk the water down” the last half mile or so of the ditch, shoveling out the leaves, brush, fallen branches, mud balls, and other accumulated winter glorp, which the flowing water tends to push up into clots that become dams, and dams that become overflows of chocolate water headed for someone’s kitchen door, maybe mine.

The work is joyous but difficult because it means the beginning of irrigation season, when we get to murmur wake up! to the sleeping fields and spread water over them. Robins come squawking, jays curse, and in a day’s time the richer green of the field wherever the water touched it shows up like a footprint.

Yesterday was also complicated by news that a family member who works in eldercare was showing early signs of COVID-19. She lives alone, at a distance from everyone else, and you can imagine the anxious phone calls that ensued, with their outpouring of advice, caution, and alarm. It was a restless night, but in the light of this glorious spring morning, it seems that her symptoms are due to a simple garden-variety ailment and that all will turn out well. May it be so.

Such is the roller-coaster of these days.

Glorious this spring morning seems to be, but I cannot recall a spring day to match the one when we took the road from your place over Lolo Pass and visited a river on the Idaho side. I remember thick-trunked trees under a forest canopy that shut out the sun. Soon we came out into dazzling brightness where boulders lined the river’s edge. You narrated the flow of the water, the variations in current, the strategies of the hungry trout in the eddies and under ledges, and the consequent logic of where a perfect cast would land a fly. It was a master class in reading water, and it ranks up there with the best looks I have ever had of that place where craft turns into art. I am ready to sign up for another.

You brought up the Freeflow Institute wilderness writers’ workshop. Such trips make me ruminate on how to approach teaching—and writing—in the midst of a pandemic. Big History is unfolding around us. We are at a pivot point of our era, and may never see the like again. Whatever new normal emerges from the present turmoil, it will be different from the old normal we just came out of. Or should we be talking about old and new abnormals?

In periods of change, you wonder what to notice, what to bear particular witness to. I keep a log of certain stats and impressions; perhaps that record will one day be a door back into memories of this crazy time. But I keep wondering what else I should include. In a “letter to students,” posted at The New Yorker website, George Saunders asks, “Are you keeping records of the e-mails and texts you’re getting, the thoughts you’re having, the way your hearts and minds are reacting to this strange new way of living? It’s all important.”

I like the sound of that, but of course, no one can keep track of everything; there aren’t enough hours in the day (and Saunders admits he doesn’t follow his own advice).

So what do we pay attention to? What are the right signs and subjects to document: corporate greed, private despair, crocuses in the garden? Does finding our way through the maze of options mean we first have to figure out what our own story is, then we can know what to let in, what to filter out? And how the hell do we zero in on that story? Which brings us back to the question that was always in front of us.

John Prine was one of the few who could give a meaningful tip, or at least tell us not to worry and just hang in there and let the answers appear. I will miss that wise and cranky so-and-so.

The other side of this is to wonder, with so much of the former status quo in flux, might there be a point of leverage, a vulnerability leading to a tipping point, where we could throw our collective weight toward the kind of change that would give the Tahlequahs of the future a better chance of keeping her baby alive? Will this crisis help us turn a corner on tending nature and cooling down the planet?

As soon as I say such things, my inner curmudgeon interrupts. What silly optimism! Haven’t you learned anything in your seventy years about human cupidity and pigheadedness?

And yet, and yet…

Hang in there, brother. Stay safe and please give my best to Adrian.

Bill

April 10, 2020

Hermano William,

My covetousness would be inexcusable if I did not happen to possess a handsome ballcap, scarcely used, with a startlingly blue raven on it, with which I will honor your sense that the gift must always move. Send me your address and we’ll find out whether switching hats causes us to sign books as William Duncan and David James deBuys.

I was happy to hear of your first day of ditch work. Your ditches captured my imagination in The Walk, a 2007 book some guy named Duncan said “forces despair to hold hands with beauty, truth, and hope.” Seems like that kind of hand-holding is the best we can do in this time in the world’s unfolding — or collapse — or both.

I share your sense that optimism can seem like sheer foolishness, but am glad to know we both inhabit a place that causes us to add, “and yet, and yet…”

I’m a world-class pessimist in response to the human predilection to seek one’s own happiness at the cost of the complete ruin of the lives of others. But I’m a world-class optimist in that I hold that reincarnation is inarguable and that karmic justice is as real as rock slides are to earthquakes.

It feels important to add that the strength of my faith is not based on my solitary worthless opinion. It’s based on the fact that some people are wildly better at certain things than almost all other people. NBA basketball, cello music, and spiritual experience are these arenas where this is obvious. I believe in LeBron James, Pablo Casals, and Meister Eckhart’s respective abilities for similar reasons.

I refuse to subscribe to the common American belief that the barely articulate superstitions of Biff Nunn, foosball champion of the upper Bitterroot Valley, are on an equal footing with the teachings of Lord Krishna, Gautama Buddha, and His Holiness the Dalai Lama just because Walmart Shoppers of The Soul have decided spiritual experience is democratic, like voting.

This is little different than believing that Biff’s knowledge of how to compose and perform a fugue in D minor, thanks to democracy, are on a par with J.S. Bach’s. Stick to foosball, Biff.

The Dalai Lama is awfully good at dislodging this kind of bunkum. In The Art of Happiness, he tells a roomful of American medical professionals who were basically a flock of democratic Biffs:

“You have the constraints of the idea that everything about a person can be explained within the framework of a single lifetime. Western psychology does not accept the idea of impressions being carried over from a past life. So, when you can’t explain what is causing certain behaviors or problems, the tendency is to always attribute it to the unconscious. No other possibility allowed! It’s a bit as if you’ve lost something, and you decide that the lost object is in this room. Once you’ve decided this, you’ve precluded the possibility of the object being outside the building or in another room. So you keep on searching and searching, and not finding it. Yet you continue to assume it is in this room!”

I resonated strongly with your volley of questions, Bill: “What do we pay attention to? What are the right signs and subjects to document: corporate greed, private despair, crocuses in the garden? Does finding our way through the maze of options mean we first have to figure out what our own story is, then we can know what to let in, what to filter out? And how the hell do we zero in on that story?”

Here’s how I zeroed in on what I’ve been doing for many years:

A number of years back, I laughed out loud when Tom McGuane, in an interview, said, “Fiction is the ditch I’ll die in.”

In 2007, scarcely knowing what I was doing, I then chose to die in the same ditch.

I was an activist writer for a good while, and was a few times wildly more successful than expected. But in the end, my complete failure to help save wild salmon and orcas despite twenty-five years of effort was a huge part of my opting for fiction. I wrote about that gigantic injustice and irreplaceable loss of wild salmon with all my heart and all my puny might. By so doing, I came to realize that I live in a world where eloquent writing, scientific facts, and ecological necessity change almost nothing that industrial civilization is determined to do.

My activism ever since has been supporting lawyers who sue the bastards.

Here is the turn that knocked me out of the Eloquent Activist Writer game:

In the year 2000, an essay of mine, “A Prayer for the Salmon’s Second Coming,” was reprinted as a 6,000-word pamphlet that inspired something like 60,000 people to fill out a Sierra Club postcard and submit it to the Army Corps, saying that the lower Snake River dams are an extinction-manufacturing travesty and calling for their removal. The Corps at the time was in charge of a survey of the Northwest’s twelve largest cities, gathering public opinion on dam removal. They collected those 60,000 postcards filled out by sincere people from every state in the Union and declared, “These are all the same postcard. These 60,000 opinions only count as one opinion.”

This logic would negate every election in history since every vote for a winner is the same vote. Allowing the Army Corps to collect opposition to the dams they build and lie about with no oversight and no one to answer to, is like hiring meth cooks to run the nation’s drug rehab programs.

I fled the insane-making inequities of that playing field in despair. And yet. And yet….

That same moment made me resonate strongly with Paul Kingsnorth when he declared himself a failed environmental activist and sought to tell a much larger and deeper story by co-writing The Dark Mountain Manifesto. It was music to my ears to read in those pages:

“What remains after the fall (of a civilization) is a wild mixture of cultural debris, confused and angry people whose certainties have betrayed them, and those forces which were always there, deeper than the foundations of the city walls: the desire to survive and the desire for meaning.”

What especially grabbed me as an artist was the recognition that “the desire to survive and the desire for meaning” are “deeper than the foundations of the city walls.”

Yes! Looking at the power that, to cite one of countless examples, George Saunders’s fantastic bardo novel generated in support of what the Dalai Lama was trying to tell the “brain chemistry is everything” people, I began to approach the kinds of questions you’re asking by reveling in the latitude fiction gives me to dance with such questions, unrestricted by the strangling and abstracted ways that NGOs approach problems.

I then gave that desire to “dance with the questions” to a single project I’ve pursued continuously since 2007, a now-massive novel called Sun House.

I studied War and Peace with Ursula LeGuin’s wonderful historian husband Charles in college and was thereby inspired to commit the folly of a 19th century Russian baseball novel called The Brothers K, but somehow failed to learn my lesson. Since Tolstoy also wrote Anna Karenina, I figured TWO GYNORMOUS NOVELS ARE POSSIBLE! and lit into Sun House.

But to pour so much into a single volume has been a terrible challenge in ways I could not see coming. One is the simple fact that I’ve written over a thousand pages of the best work I’ve ever done, and no one outside a small circle of trusted friends has seen a word of it.

Nowadays I get notes that might once have been fan letters saying, “Dear David James Duncan, Are you dead? You sure publish like you are! Where the fuck are you? What is going on?!”

I’m currently forty pages of composing and 200 pages of editing from completion, and this book will say every considered thing I can articulate about “the desire to survive and the desire for meaning” found by calling on “sources far deeper than the foundations of city walls.”

But what a sanity-challenger my long solitude has been.

The upside: perhaps my long effort has made me worthy of an OLDER THAN DIRT cap.

How strange to say that, after several days in the sixties, with dead calm winds, we face a winter storm warning starting at midnight, with snow, forty-five mile-per-hour winds, and two days with lows of eighteen degrees.

Thanks for a splendid letter, and for the good word to Adrian.

David

April 11, 2020

‘Mano David,

When Sun House comes out, I will be among its first readers. Good on ya’ for staying the course.

Your epic wrestling match with that monster recalls what Uncle Herman (Melville) exclaimed in relation to a pretty big book that he wrote: “O Time, Strength, Cash, and Patience!” May you continue to be adequately supplied in all four departments.

What a pleasure it has been to have this chat with you and that I hope our actual corporeal paths will cross again soon. The hat is on its way to you in custody of the USPS, and my coordinates are on the address label. Should you send along the topper you mentioned, I would be honored to wear the sign of the raven.

A closing comment: you mentioned Meister Eckhart. I revere him for a humble admission he is said to have made toward the end of a long life of contemplation. Someone asked him if God had ever spoken to him. No, he replied, never anything so clear. But once or twice, Eckhart allowed, he might have heard God clear His throat.

Take that, Billy Graham, Jr.

(Or maybe it was Her throat or Its throat or Their throat, but what do we know?)

Keep an ear out, brother. There are noises blowing around that we don’t know we hear.

Un abrazo fuerte,

Bill

April 11, 2020

Dear Bill,

I also like your Eckhartian reminder that humility may be even more important than utility, and silence may be the Unseen’s only truly trustworthy speech.

Regarding Eckhart’s humble words, I lean toward “Her throat.” I don’t have answers as to why. Only questions. But lots of those! Sticking with deified and feminine pronouns just to see how it feels:

What if, just as Mother Earth appears to be dying a death of a billion cuts, She is secretly giving birth in a billion ways so infinitesimal and subtle that the birth process may take as long as the death process, and centuries will pass before we begin to make out the infant Earth She is bequeathing us?

What if Her death pangs are being experienced by animals, birds, plants, glaciers, ice caps, forests, coral reefs, and humans as catastrophic, and we’re in for some rough centuries, but in the end, the Sixth Great Extinction will prove no more final than the first five?

What if a human-created Industrial Monster that has laid waste to Earth for centuries is subject to karmic law? And what if, due to this law, the Monster cannot much longer exist on a planet it has nearly finished killing, because soon She’ll be unable to feed it? What if the Monster’s self-caused doom is now bearing down upon it with a speed and force so great it has no more chance to adjust to it than polar bears could adjust to life in the Sahara?

What if the worst of the alpha male multi-billionaires and their lobbyists and pet Senators and Supreme Court justices are sunk so deep in a senile faux reality that, starting in the year 2010, they equated the lifeless paper tokens called dollars with living human hearts and declared the corporate entities squatting atop the world’s largest dollar heaps to be living beings they are sworn to protect, though this ”protection” quickly brought about the end of representative democracy and continues to ruin millions of human and nonhuman lives?

What if Mother Earth seems cruel at this moment in time because She was left out of the conversation by Industrial Man for fatal centuries, forcing Her to bring our planet back into balance by Her own means whether fact-&-science-&-civility-&-compassion-spurning industrial plutocrats like those means or not?

What if, as our man Eckhart says, When the soul wants to experience something, she throws an image out in front of her, then steps into it?

What if a whole lot of us yearn to step out our doors in the morning onto a planet in balance and health exercising guidance over our actions from dawn to dark, rather than commute to a shit job foisted upon us by those same plutocrats lusting for wealth, regardless of Earth’s needs?

What if, unlike her creatures, Earth isn’t at all panicked by what industrial humanity has done to Her? What if Her superheated heart core is fully intact, only Her surface is stricken, and She knows exactly what moves She must make to heal what has been stricken, with no concern for linear human time scales or GDP but absolute concern for our future planetary well-being?

What if, as Julian of Norwich told us, “Christ said not, Thou shalt not be tempested, thou shalt not be travailed, thou shalt not be dis-eased; but he said, Thou shalt not be overcome. And all manner of wounded and vanished things shall be well”?

No answers here, Bill. But I obviously do like questions that seek guidance from forces “deeper than the foundations of the city walls.”

In closing, I’ve learned this too: being “Together Apart” is possible, and can lead to cool new ballcaps. What a pleasure to meet up again. Best of luck to us and all manner of beings, and I hope to see you in New Mexico before too long.

David

About the Authors:

William deBuys is the author of nine books (and a tenth due out next year with Seven Stories Press), including A Great Aridness: Climate Change and the Future of the American Southwest and The Walk. He has long been involved in environmental affairs in the Southwest and was founding chair of the Valles Caldera Trust (2001-2005), which administered the 87,000-acre Valles Caldera National Preserve in New Mexico.

David James Duncan is the author of the novels The River Why and The Brothers K, the story collection River Teeth, and two nonfiction collections. His work has appeared in numerous national anthologies, including Best American Essays (twice), Best American Sportswriting, and Best American Spiritual Writing (five times). Duncan is widely renowned as an activist and expert fly fisherman. He lives with his family in western Montana.

More Resources:

- Enjoy the first two Together Apart exchanges: Amy Irvine and Pam Houston; Krista Tippett and Pádraig Ó Tuama.

- Read previous Orion contributions by deBuys and Duncan.

- Subscribe or renew to Orion today.